| Tamarind - Tamarindus indica | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Fig. 1  Ripe tamarind, Tamarindus indica Fig. 2  Tamarind: pod, pulp and seeds  Fig. 3 Amli leaves. Leaves paripinnate up to 15 cm long, rachis slender, channeled, leaflets 10-20 pairs, subsessile, oblong.  Fig. 10  T. indica L.  Fig. 11   Fig. 12  T. indica flower, Eyasi, Tanzania  Fig. 13 T. indica flower habit  Fig. 17  T. indica leaf and fruit, Eyasi, Tanzania  Fig. 18   Fig. 19   Fig. 20  T. indica (Tamarind). Leaves flowers and seedpods, Waiehu, Maui, Hawai'i.  Fig. 21  T. indica L. fruit  Fig. 22   Fig. 23  Tamarinds (T. indica) from Thailand, pods shucks, flesh fruit and pips  Fig. 29  Shelled tamarind pods  Fig. 31  Young tree, Costa Rica  Fig. 32   Fig. 33  T. indica at Ala Moana Beach Park in Honolulu  Fig. 34  Giant tree of tamarind T. indica in Ayutaya, Thailand  Fig. 35  Fig. 36  Flowers and leaves Public Market Malolos Historic Town Center and Heritage District of Barangay Santo Rosario Caniogan, Philippines.  Fig. 37  Tamarind rice - a popular rice dish from South India  Fig. 38  Horse gram tamarind gravy  Fig. 39  Tamarind candy pieces are wrapped in cellophane. They should be kept in the cupboard inside a plastic bag. It is a very spicy sweet.  Fig. 40  Tamarind (T. indica) pods and pulp for sale, market in Baubau City, Buton Island, Indonesia  Fig. 41  Tamarindo De Playa  Fig. 54  Tamarind sold at a rural market near the village of Mae On, Chiang Mai province, Thailand  Fig. 55  Ring-tailed lemur eating tamarind fruit, America's Teaching Zoo, Moorpark College |

Scientific

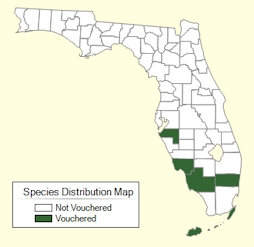

name Tamarindus indica Pronunciation tam-uh-RIN-dus IN-dih-kuh 1 Common names English: Indian tamarind, kilytree, tamarind; Spanish: tamarindo; French: tamarin, tamarin des Bas, tamarinier, tamarindier; Portuguese: tambarina, tamarindeiro, tâmara-da-Índia, tamarinda, tamarindo, tamarindo-do-Egito, tamarino; Bangladesh: amli; Brazil: cedro-mimoso; jabaí, jabao, tamarindeira-da-índia; tamarindeiro; tamarindo; tamarineira; tamarineiro; tamarinha; tamarinheiro; tamarinho; Cambodia: 'am' pul; ampil; khoua me; Germany: Tamarindenbaum, Tamarinde, Indischer; Indonesia: asam jawa; assam; tambaring; Laos: khaam; mak kham; Malaysia: asam jawa; Myanmar: magyee; majee-pen; Netherlands: tamarindeboom; Pakistan: imli; Philippines: kalamagi; salomagi; sampalok; Sri Lanka: siyambala; Thailand: bakham; makham; somkham; Vietnam: me; trai me; India: amali; ambali; ambli; amilam and more local names; Fijian: tamalina; Hindi: imli; Maori (Cook Islands): kavakava, tāmerēni; Niuean: fitihetau, tamaleni; Tahitian: tāmerēni; Tamil: puli; Tongan: tamaline; Swedish: tamarind 11,12,15 Synonyms T. occidentalis Gaertn, T. officinalis Hook 10 Relatives Royal poinciana, Delonix regia; peacock flower Cesalpiniaa pulcherrima 9 Family Fabaceae⁄Leguminosae (pea family) Origin Native to tropical Africa and Madagascar 1 USDA hardiness zones 10A-11 1 Uses Street without sidewalk; shade; specimen; parking lot island > 200 sq ft (61 sq m); tree lawn > 6 ft (1.8 m) wide; highway median 1 Height 40-65 ft (12-19.8 m) 1 Spread 40-65 ft (12-19.8 m) 1 Crown Vase shape; round; dense (Fig. 4) 1 Growth rate Slow growing tree Longevity May live to 150 years 4 Trunk/bark/branches Branches droop; showy; typically one short trunk; bark gray brown to blackish and rough; vertical fissures; horizontal cracks 1 Pruning requirement Needed for strong structure 1 Leaves Evergreen; alternate; even-pinnately compound; 3-6 in (7.5-15 cm) in length, each having 10-20 pairs of oblong leaflets 1/2 to 1 in (1.25-2.5 cm) long and 1/5 to 1/4 in (5-6 cm) 1,4 Flowers Pale yellow, reddish pink veins; 3 petals; in clusters on 6 in. (15.2 cm) pendulant raceme 1 Fruit Indehiscent pod; 2-7 in. (5-17.8 cm); dry or hard; velvety; turns green to brown when mature 1 Season Apr.-July; will keep on the tree for six months 21 Light requirement Sun 1 Soil tolerances Clay; sand; loam; alkaline; acidic; well-drained 1 pH preference Prefers 5.5-6.5; tolerating 4.5-8.5 6 Drought tolerance High 1 Aerosol salt tolerance Withstands salt spray and can be planted fairly close to the seashore 4 Wind tolerance Twigs and branches of tamarind are very resistant to wind, making it especially useful as a shade or street tree for breezy locations 1 Cold tolerance Can survive down to about 26.2 °F (-3 °C); young growth can be severely damaged at 30 °F (-1 °C) 6 Plant spacing 33-65 ft (10-20 m) between trees each way 4 Roots Extensive root system, which makes them very tolerant of windy conditions (including salt-laden winds) and drought 2 Invasive potential * Not considered a problem species at this time, may be recommended 1 Pest resistance Free of serious pests and diseases 1 Known hazard Flour from the ground seeds can cause asthma and contact dermatitis 17 Reading Material Tamarindus indica: Tamarind, University of Florida pdf Tamarindus indica L., PROSEA foundation Tamarind, Tamarindus indica, Southampton Centre for Underutilised Crops pdf Tamarind, Fruits of Warm Climates Tamarind, California Rare Fruit Growers Tamarindus indica L., Agroforestree Database Origin/Distribution It is generally believed to be indigenous to the drier savannahs of tropical Africa, but certainly became naturalized long ago in tropical Asia. The species was known and cultivated in Egypt as early as 400 B.C. Early Arab and Persian merchants came across the tree while trading in India. It is assumed that these Arabian seafarers and traders brought the seeds to Southeast Asia in very early times. Marco Polo mentions the tree in the year 1298. In the Indian Brahmasamhita scriptures, the tree is mentioned between 1200 and 200 B.C., and in Buddhist sources from about the year A.D.650. T. indica is now cultivated in all tropical countries, and it is economically important all over Southeast Asia. It was introduced to the tropics in the western hemisphere in more recent times, probably during the early years of the West African slave trade. The capital of Senegal, Dakar, was named after the local word 'dakhar' for T. indica. 2 It was introduced early into tropical America. It succeeds in southern Florida and has been grown in that state as far north Manatee, where a large tree was killed in the freeze of 1884. 8 In all tropical and near-tropical areas, including South Florida, it is grown as a shade and fruit tree, along roadsides and in dooryards and parks. 4 Description The tamarind, a slow-growing, long-lived, massive tree (reaches, under favorable conditions, a height of 80 or even 100 ft (24-30 m), and may attain a spread of 40 ft (12 m) and a trunk circumference of 25 ft (7.5 m). It is highly wind-resistant, with strong, supple branches, gracefully drooping at the ends, and has dark-gray, rough, fissured bark. 4 T. indica is a monospecific genus. In the past a distinction was made between tamarinds from the West and the East Indies: West Indies: T. occidentalis: pod up to 3 times longer than wide, containing 1-4 seeds; East Indies: T. indica: pod up to 6 times or more longer than wide, containing 6-12 seeds. 3 Tamarind is not very compatible with other plants because of its dense shade, broad spreading crown and allelopathic effects. The dense shade makes it more suitable for firebreaks as no grass will grow under the trees. 2 Almost all parts of the plant are used, particularly the pulp of the fruit and young leaves which are regarded as important ingredients of many tasty dishes. Pulp of the fruit, seeds, leaves, flowers and bark are also put to various medicinal uses. 5 The much-appreciated qualities of the tamarind and its adaptability to different soils and climates enabled it to conquer the tropics in the remote past; the tree and its fruit are still highly prized today. It is, therefore, all the more surprising that so little is known about tree phenology, floral biology, husbandry, yield and genetic diversity. 3

Fig. 4. T. indica in Matictic-Pinagtulayan, Norzagaray, Bulacan Farm to Market Road (Philippines) Fig. 5. T. indica, Herbier numérique du parc urbain Bangr-Weoogo Ouagadougou Fig. 6. Tamaryndowiec indyjski (T. indica) Leaves The mass of bright-green, fine, feathery foliage is composed of pinnate leaves, 3 to 6 in (7.5-15 cm) in length, each having 10 to 20 pairs of oblong leaflets 1/2 to 1 in (1.25-2.5 cm) long and 1/5 to 1/4 in (5-6 mm) wide, which fold at night. 4 Petiole and rachis are finely haired, midrib and net veining more or less conspicuous on both surfaces; apex rounded to almost square, slightly notched; base rounded, asymmetric, with a tuft of yellow hairs; margin entire, fringed with fine hairs. Stipules present, falling very early. 2

Fig. 9.Tamarind leaves, Citrus grove Sand Island, Midway Atoll, Hawai'i Flowers Inconspicuous, inch-wide flowers, borne in small racemes, are 5-petalled (2 reduced to bristles), yellow with orange or red streaks. The flowerbuds are distinctly pink due to the outer color of the 4 sepals which are shed when the flower opens. 4 Flowering generally occurs in synchrony with new leaf growth, which in most areas is during spring and summer. Terminal vegetative shoots which bear flowers only in the following flowering season are produced annually. 2,14 The flowers can be bisexual, as well as dichogamous and protogynous. Flower-bud development takes about 20 days from the first visible initiation. The period from flowering to pod ripening is 8-10 months. Ripe fruits, however, may remain on the tree until the next flowering period. 14,16

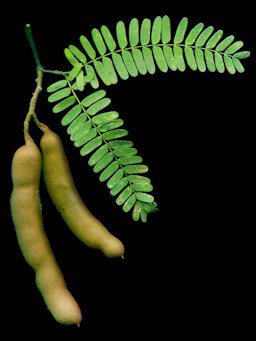

Fruit Fruit are leathery, nutritive pods that do not dehisce until they have fallen from the tree, while the seeds are hard and smooth and therefore hard to chew. 2 Fruit a pod, indehiscent, subcylindrical, 4-7 x 1.8 in. (10-18 x 4 cm), straight or curved, velvety, rusty-brown; the shell of the pod is brittle and the seeds are embedded in a sticky edible pulp. Seeds 3-10, approximately 0.6 in. (1.6 cm) long, irregularly shaped, testa hard, shiny and smooth. As the dark brown pulp made from the fruit resembles dried dates, the Arabs called it 'tamar hindi', meaning date of India, and this inspired Linnaeus when he named the tree in the 18th century. 2

Fig. 24. T. indica (Tamarind), seedpods, Hawea Pl Olinda, Maui, Hawai'i Fig. 25. Pulp, Hawea Pl Olinda, Maui, Hawai'i Fig. 26. Variation in dark red and brown pulp colour in tamarind Fig. 27. T. indica L., Indian date. Pulp Fig. 28. T. indica L., Indian date. Seeds

"Gooey-sweet fruit candy grows on a tree - this is sweet tamarind. I'm a sucker for super sweet fruits, so I'm loving the fact that this tropical delicacy has become widely available in the last few years. Tamarind is a tree in the bean family, so it's a distant cousin of lentils & limas. But tamarind definitely qualifies as a FRUIT - it has a rich, fruity, sweet tart flavor, and it's the pulp you eat, not the seeds. The pulp naturally dehydrates into a sweet, sticky paste inside the dry, papery shell, with a several hard seeds enclosed within the paste." 20 Varieties In some regions the type with reddish flesh is distinguished from the ordinary brown-fleshed type and regarded as superior in quality. There are types of tamarinds that are sweeter than most. One in Thailand is known as 'Makham waan'. One distributed by the United States Department of Agriculture's Subtropical Horticulture Research Unit, Miami, is known as 'Manila Sweet'. 4 There are wide differences in fruit size and flavor in seedling trees. Indian types have longer pods with 6 - 12 seeds, while the West Indian types have shorter pods containing only 3 - 6 seeds. Most tamarinds in the Americas are of the shorter type. 7 Season Mexican studies reveal that the fruits begin to dehydrate 203 days after fruit-set, losing approximately ½ moisture up to the stage of full ripeness, about 245 days from fruit-set. In Florida, Central America, and the West Indies, the flowers appear in summer, the green fruits are found in December and January and ripening takes place from April through June. In Hawaii the fruits ripen in late summer and fall. 4 Harvesting In the Philippines, the fruits of sour types are harvested at 2 stages: green for flavouring and ripe for processing. Fruits of sweet cultivars are also harvested at 2 stages: half ripe or 'malasebo' stage and ripe stage. At the half-ripe stage the skin is easily peeled off; the pulp is yellowish-green and has the consistency of an apple. At the ripe stage, the pulp shrinks because of loss of moisture, and changes to reddish-brown and becomes sticky. If the whole pod is to be marketed, the fruit should be harvested by clipping to avoid damaging the pods. Eventually the pods abscise naturally. 3 Green fruits for cooking, and half-ripe and ripe fruits for fresh consumption are sold by weight in the markets. Ripe fruits for processing are peeled, fibre strands are removed, and then they are sold by weight in plastic containers. The fruit of sweet cultivars commands a much higher price than the sour fruit. 3 Tamarinds may be left on the tree for as long as 6 months after maturity so that the moisture content will be reduced to 20% or lower. 4 Pollination Studies carried out in Sri Lanka revealed that tamarind pollen grains are sticky and the flowers produce nectar. Sticky pollens are not efficient for wind pollination. Honey bees (Apis spp.) are common visitors to tamarind flowers particularly between 08.00-11.00 hrs and 16.00-18.00 hrs. Observations of honey bee activity on flowers and their visitation patterns suggest that they are effective pollinators. Thus, pollination is mostly by honey bees. 14 Fruit Development Fruit development in tamarind has three distinct stages: growth, maturation and ripening. The indehiscent pods ripen about 8-10 months after flowering and may remain on the tree until the next flowering period (Benthall, 1933; Chaturvedi, 1985; Rama Rao, 1975). In Mexico the fruits begin to dehydrate 203 days after fruit set and continue until 245 days when full ripeness occurs and up to half the fruit’s original water content is lost. The fully ripened fruits can remain on the tree for six months. 14 Propagation The seeds remain viable for many months and germinate within 1-2 weeks after sowing. Growth is generally slow, seedling height increasing by about 60 cm annually. The juvenile phase lasts 4-5 years or longer. 3 If quality fruit is desired, plants should be air-layered, grafted, or shield-budded. 1 Fruits are adapted to dispersal by ruminants; in Southeast Asia, monkeys are among the chief dispersal agents. T. indica usually starts bearing fruit at 7-10 years of age, with pod yields stabilizing at approximately 15 years. 2

Fig. 30. An emerging tamarind tree seedling, Kerala, India Culture Tamarind grows well over a wide range of soil and climatic conditions. It is found in places with sandy to clay soils, at low to medium altitudes (up to 1000 m, sometimes to 1500 m), where rainfall is evenly distributed or where the dry season is long and very pronounced. Its extensive root system contributes to its resistance to drought and strong winds. In the wet tropics (rainfall > 4000 mm) the tree does not flower, and wet conditions during the final stages of fruit development are detrimental. 3 The tree bears abundantly up to an age of 50-60 years or sometimes longer, then productivity declines, though it may live another 150 years. 4 Pruning Initial training and pruning of young plants during the first years is essential for the development of well-formed trees. Tamarind is a compact tree and produces symmetrical branches. Young trees should be pruned to allow 3-5 well-spaced branches to develop into the main scaffold structure of the tree. 14 After this, only maintenance pruning is required to remove dead or damaged wood. 2 Fertilization Tamarind trees fruit well with or without the application of fertilizer due to their deep and extensive root system. Urea at 100-200 g/tree is applied to commercially grown tamarind to support high yields. The amount of fertilizer can be gradually increased as the trees grow. Additional nutrition can be applied when the trees begin to bear fruit. 19 Irrigation Young trees require adequate soil moisture until they become established, but mature trees do quite well without supplemental irrigation. Avoid over-watering which results in soggy soils. 7 Pests/Diseases No serious insect or disease problems. Occasional insect problems include scale, mealybug, fruit borers, caterpillars, aphids and thrips. Occasional disease problems include leaf spots and rot. 16 Food Uses The fruit pulp, mixed with a little salt, is a favourite ingredient of the curries and chutneys popular throughout India, though most of the tamarind imported into Europe today comes from the West Indies, where sugar is added as a preservative. When freshly prepared, the pulp is a light brown colour but darkens with time; it consists of 8-14% tartaric acid and potassium bitartrate, and 30-40% sugar. The ripe fruit of the sweet type is usually eaten fresh, whereas the fruits of sour types are made into juice, jam, syrup and candy. Fruit is marketed worldwide in sauces, syrups and processed foods. The juice is an ingredient of Worcestershire Sauce and has a high content of vitamin B (thiamine and niacin) as well as a small amount of carotene and vitamin C. The flowers, leaves and seeds can be eaten and are prepared in a variety of dishes. Tamarind seeds are also edible after soaking in water and boiling to remove the seed coat. Flour from the seed may be made into cake and bread. Roasted seeds are claimed to be superior to groundnuts in flavour. 2 Young leaves and very young seedlings and flowers (Fig. 36) are cooked and eaten as greens and in curries in India. In Zimbabwe, the leaves are added to soup and the flowers are an ingredient in salads. 4

Fig. 42. Jamaican snack Fig. 43. Tamarind products, Dhaka, Bangladesh Fig. 44. A bowl of salted tamarind Fig. 45. Balls of candy made from tamarind Fig. 46. Dahi Bhalla Chaat, Indian snack Fig. 47. Tamarind shrimp, also known as Assam prawns Fig. 48. Agua de tamarindo Tamarind Recipes, Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden, Virtual Herbarium Database Nutrient Content Ripe fruits have 40—50% edible pulp which contains per 100 g: water 17.8—35.8 g, protein 2—3 g, fat 0.6 g, carbohydrates 41.1—61.4 g, fibre 2.9 g, ash 2.6—3.9 g, calcium 34—94 mg, phosphorus 34—78 mg, iron 0.2—0.9 mg, thiamine 0.33 mg, riboflavin 0.1 mg, niacin 1.0 mg and vitamin C 44 mg. Fresh seeds contain 13% water, 20% protein, 5.5% fat, 59% carbohydrates and 2.4% ash. The acidity is caused by tartaric acid, which on ripening does not disappear but is matched more or less by increasing sugar levels. Hence tamarind is said to be simultaneously the most acid and the most sweet fruit. 3 The seeds are gaining importance as a rich source of protein with a favorable amino acid composition. This cheap source of protein can alleviate protein malnutrition widespread in many of the developing nations. It also has potential for substituting at least 30% of cereals in livestock rations. 18 Medicinal Properties ** Ripe tamarind fruit has a widely recognized and proven medicinal value. The American pharmaceutical industry processes 100 t of tamarind pulp annually. The fruit is said to reduce fever and cure intestinal ailments. Its effectiveness against scurvy is well documented. It is a common ingredient in cardiac and blood sugar-reducing medicines (Von Maydell, 1986). The pulp is also used as an astringent on skin infections. 18 Other Uses Kernels are powdered and are used in the Indian textile industry as starch. This proves to be a very cost effective deal as the tamarind seed powder is 300% more efficient than corn starch and is extremely economical. The techniocal advantages of using kernel powder in the sizing and finishing cotton, jute and spun viscose are effectively high.13 Seed powder is also used in various other industrial purposes such as color printing of textiles, paper sizing, leather treating, manufacture of a structural plastic, a glue for wood, a stabilizer in bricks, a binder in sawdust briquettes, and a thickener in some explosives, etc. 13 Fodder: The foliage has a high forage value, though rarely lopped for this purpose because it affects fruit yields. In the southern states of India cooked seeds of Tamarind tree are fed to draught animals regularly. Apiculture: Flowers are reportedly a good source for honey production.The second grade honey is dark-coloured. Fuel: Provides good firewood with calorific value of 4 850 kcal/kg, it also produces an excellent charcoal. Timber: Sapwood is light yellow, heartwood is dark purplish brown; very hard, durable and strong (specific gravity 0.8-0.9g/cubic m), and takes a fine polish. It is used for general carpentry, sugar mills, wheels, hubs, wooden utensils, agricultural tools, mortars, boat planks, toys, panels and furniture. In North America, tamarind wood has been traded under the name of 'madeira mahogany'. Lipids: An amber coloured seed oil - which resembles linseed oil - is suitable for making paints and varnishes and for burning in lamps. Tannin or dyestuff: Both leaves and bark are rich in tannin. The bark tannins can be used in ink or for fixing dyes. Leaves yield a red dye, which is used to give a yellow tint to clothe previously dyed with indigo. Ashes from the wood are used in removing hair from animal hides. Other products: The pulp of the fruit, sometimes mixed with sea-salt, is used to polish silver, copper and brass in India and elsewhere. The seed contains pectin that can be used for sizing textiles. Ground, boiled, and mixed with gum, the seeds produce a strong wood cement. In Africa, tamarind is a host of one of the wild silkworms (Hypsoides vuillitii). 2

Fig. 49. Exposing the wood under the bark Fig. 50. Bowl made of tamarind wood Tamarind seed processing and by-products, CIGR Journal pdf General Blood-red gum exudes from the bole (trunk) and branches when damaged. 18 The fruit contains the richest natural source of tartaric acid (8-10%) of any fruit. 19 The strong, pliant branches and deep, extensive root system of the tamarind tree, which anchors it to the ground during strong winds, violent tycoons and cyclones, have earned the tree the title of the 'hurricane-resistant' tree (NSA, 1979). 19

Fig. 51. The 186th Annual Flower Show was held at the garden of the Agri-Horticultural Society of India. Fig. 52. Bonsai in the Morikami Museum and Japanese Gardens - Palm Beach County, Florida, USA.

Further Reading Tamarind, Manual Of Tropical And Subtropical Fruits Tamarind, Common Forest Trees of Hawai'i, USDA pdf Tamarindus indica, Floridata Botanical Art List of Growers and Vendors |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bibliography 1 Gilman, Edward F., et al. "Tamarindus indica: Tamarind." Environmental Horticulture Dept., UF/IFAS Extension, ENH776 Original pub. Nov. 1993, Rev. Mar. 2007 and Dec. 2018, EDIS, edis.ifas.ufl.edu/st618. Accessed 6 Feb. 2020. 2 "Tamarindus indica L." Tree Species, Agroforestry Database, db.worldagroforestry.org/species/properties/Tamarindus_indica. Accessed 6 Feb. 2020. 3 Coronel, R. E, "Tamarindus indica L." Edible fruits and nuts, Plant Resources of South-East Asia No 2, Edited by E. W. M. Verheij, and R. E. Coronel, PROSEA Foundation, Bogor, Indonesia, record 1530, 1991, PROSEA, (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0), www.prota4u.org/prosea/view.aspx?id=1550. Accessed 7 Feb. 2020. 4 Fruits of Warm Climates. Julia F. Morton. Miami, 1987. 5 "Tamarind, Tamarindus indica L." Flora of Pakistan, Encyclopedia of Life, via eFloras, Missouri Botanical Garden, 4344 Shaw Boulevard, St. Louis, MO, 63110 USA, EOL, (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0), eol.org/pages/639027/articles. Accessed 12 Feb. 2020. 6 "Tamarindus indica L." Plants for a Future, via Ecocrop, PFAF, (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0), pfaf.org/user/Plant.aspx?LatinName=Tamarindus+indica. Accessed 14 Feb. 2020. 7 "Tamarind." California Rare Fruit Growers, crfg.org/wiki/fruit/tamarind/. Accessed 14 Feb. 2020. 8 Popenoe, Wilson. Manual Of Tropical And Subtropical Fruits. 1920, London, Hafner Press, 1974. 9 Christman, Steve. "Tamarindus indica." Floridata, 19 Dec. 2000, Updated 2 Feb. 2004, floridata.com/plant/891. Accessed 15 Feb. 2020. 10 "Synonyms for Tamarindus indica L." The Plant List (2013), Version 1.1, www.theplantlist.org/tpl1.1/record/ild-1720. Accessed 15 Feb. 2020. 11 "Tamarindus indica (Indian tamarind)." CABI, Invasive Species Compendium, www.cabi.org/isc/datasheet/54073. Accessed 19 Feb. 2020. 12 "Tamarindus indica L." Pacific Island Ecosystems at Risk, (PIER), www.hear.org/pier/species/tamarindus_indica.htm. Accessed 19 Feb. 2020. 13 "Tamarind Seeds: Uses of Tamarind Seeds." Agro Products, www.agriculturalproductsindia.com/seeds/seeds-tamarind-seeds.html. Accessed 20 Feb. 2020. 14 El-Siddig, K, et al. "Tamarind, Tamarindus indica." Fruits for the Future 1, Revised edition, 2006, Southampton Centre for Underutilised Crops, Southampton, UK, The National Archives, www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/webarchive. Accessed 20 Feb. 2020. 15 "Taxon: Tamarindus indica L." USDA, Agricultural Research Service, National Plant Germplasm System, Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN-Taxonomy), National Germplasm Resources Laboratory, Beltsville, Maryland, 2019, U.S. National Plant Germplasm System, npgsweb.ars-grin.gov/gringlobal/taxonomydetail.aspx?id=36219. Accessed 21 Feb. 2020. 16 "Tamarindus indica." Missouri Botanical Garden, www.missouribotanicalgarden.org/PlantFinder/PlantFinderDetails.aspx?taxonid=280489. Accessed 21 Feb. 2020. 17 "Tamarindus indica L." Kew Species Profiles, Plants of the World Online, Facilitated by the Royal Botanic Gardens, POWO, (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0), www.plantsoftheworldonline.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:520167-1. Accessed 21 Feb. 2020. 18 Paull, Robert E. and Odilo Duarte. Tropical Fruits, Volume I. 2nd ed., Cambridge, CABI, 2011. 19 The Encyclopedia of Fruit & Nuts. Edited by Jules Janick and Robert E. Paull, Cambridge, CABI, 2008. 20 Hepworth, Craig. "Tamarind." Florida Fruit Geek, floridafruitgeek.com/. Accessed 7 Feb. 2020. 21 "Tamarind." Gardening Solutions, UF/IFAS, gardeningsolutions.ifas.ufl.edu/plants/edibles/fruits/tamarind.html. Accessed 10 Dec. 2020. Video v Hepworth, Craig. "Tamarind." Florida Fruit Geek, floridafruitgeek.com. Accessed 7 Feb. 2020. Photographs Fig. 1 Pixabay, Public Domain, pixabay.com/photos/tamarind-isolated-ripe-spice-1549223/. Accessed 17 Feb. 2020. Fig. 2 Jungle Rebel. "Tamarind: pod, pulp and seeds." Commons Wikimedia, 23 Feb. 2012, (CC BY-SA 3.0), commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tamarindus_Indica_(Thailand).JPG. Accessed 19 Feb. 2020. Fig. 3 Pankag, Oudhia."Amli leaves. Leaves paripinnate up to 15 cm long, rachis slender, channeled, leaflets 10-20 pairs, subsessile, oblong." Ecoport, 46655, 6 Aug. 2005, ecoport.org/ep?SearchType=pdb&PdbID=46655. Accessed 21 Feb. 2020. Fig. 4 Judgefloro. "Tamarandus indica in Matictic-Pinagtulayan, Norzagaray, Bulacan Farm to Market Road." Enclyclopedia of Life, via Wikimedia Commons, 46083674, 3 Jan. 2016, EOL, (CC BY-SA 3.0), eol.org/pages/639027/media. Accessed 12 Feb. 2020. Fig. 5 Castello, Enrico. "Tamarandus indica. Herbier numérique du parc urbain Bangr-Weoogo Ouagadougou." iNaturalist, 3883412, 25 Jan 2002, (CC BY-NC), www.inaturalist.org/photos/3883412. Accessed 12 Feb. 2020. Fig. 6 Kwiecień, Agnieszka. "Tamaryndowiec indyjski (Tamarindus indica)." Commons Wikimedia, (CC-BY 3.0), Derivative work, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Owoce_Oliwka.jpg. Accessed 19 Feb. 2020. Fig. 7,21 Janzen, Daniel J. "Tamarindus indica L." Guanacaste Dry Forest Conservation Fund, via Flickr, 2010, EOL, (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0), Image cropped, eol.org/pages/639027/media. Accessed 12 Feb. 2020. Fig. 8,31 Aguilar, Reinaldo. "Tamarindus indica L." Vascular Plants of the Osa Peninsula, Costa Rica, via Flickr, 7144733293, EOL, (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0), eol.org/pages/639027/media. Accessed 12 Feb. 2020. Fig. 9 Starr, Forest and Kim. "Tamarindus indica (Tamarind). Leaves, Citrus grove Sand Island, Midway Atoll, Hawai'i." Starr Environmental, 080608-7474, 8 June 2008, (CC BY 4.0), www.starrenvironmental.com/images/image/?q=24798368782. Accessed 15 Feb. 2020. Fig. 10,15 Bradley, Keith. "Tamarindus indica L." Institute for Systematic Botany, University of South Florida, Tampa, S. M. Landry and K. N. Campbell (application development), USF Water Institute, 2019, Atlas of Florida Plants, florida.plantatlas.usf.edu/photo.aspx?ID=2047. Accessed 12 Feb. 2020. Fig. 11,19,35 Boatman, Allen. "Tamarindus indica L." Institute for Systematic Botany, University of South Florida, Tampa, S. M. Landry and K. N. Campbell (application development), USF Water Institute, 2019, Atlas of Florida Plants, florida.plantatlas.usf.edu/photo.aspx?ID=2047. Accessed 12 Feb. 2020. Fig. 12 Bygott, David. "Tamarindus indica flower, Eyasi, Tanzania." Encyclopedia of Life, via Flickr, 4329720988, Nov. 2002, EOL, (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0), eol.org/pages/639027/media. Accessed 12 Feb. 2020. Fig. 13 Hernández, Andrés. "Tamarindus indica." Digital File Manager, Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, no. 28326, STRI, biogeodb.stri.si.edu/bioinformatics/dfm/metas/view/28326. Accessed 19 Feb. 2020. Fig. 14 Rakotoarisoa, Solofo Eric."Tamarandus indica." Encyclopedia of Life, via iNaturalist, 2755719, 26 Nov. 2015, EOL, (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0), eol.org/pages/47317872/media. Accessed 12 Feb. 2020. Fig. 16 Lalithamba. "Tamarindus indica flower, Eyasi, Tanzania." Encyclopedia of Life, via Flickr, 4912351397, 21 Aug. 2010, EOL, (CC BY 2.0), eol.org/pages/639027/media. Accessed 12 Feb. 2020. Fig. 17 TamEOL.jpg Bygott, David. "Tamarindus indica leaf & fruit, Eyasi, Tanzania." Encyclopedia of Life, via Flickr, 4329720988, Nov. 2002, EOL, (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0), eol.org/pages/639027/media. Accessed 12 Feb. 2020. Fig. 18 TamAtlasFL6.jpg Kunzer, John. "Tamarindus indica L." Institute for Systematic Botany, University of South Florida, Tampa, S. M. Landry and K. N. Campbell (application development), USF Water Institute, 2019, Atlas of Florida Plants, florida.plantatlas.usf.edu/photo.aspx?ID=2047. Accessed 12 Feb. 2020. Fig. 20 Starr, Forest and Kim. "Tamarindus indica (Tamarind). Leaves flowers and seedpods, Waiehu, Maui, Hawai'i." Starr Environmental, 090720-2973, 20 July 2009, (CC BY 4.0), www.starrenvironmental.com/images/image/?q=24339405314. Accessed 15 Feb. 2020. Fig. 22 Baumann, Günter."Tamarind pods." West African Plants, EOL, (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0), eol.org/pages/639027/media. Accessed 12 Feb. 2020. Fig. 23 TamEOL7.jpg Carschten. "Tamarinds (Tamarindus indica) from Thailand, pods shucks, fruit flesh and pips." Enclyclopedia of Life, via Wikimedia Commons, 17003043, 5 Aug. 2011, EOL, (CC BY 2.0), eol.org/pages/639027/media. Accessed 12 Feb. 2020. Fig. 24 TamStarr4.jpg Starr, Forest and Kim. "Tamarindus indica (Tamarind). Seedpods, Hawea Pl Olinda, Maui, Hawai'i." Starr Environmental, 120627-7645, 27 June 2012, (CC BY 4.0), www.starrenvironmental.com/images/image/?q=24558781123. Accessed 15 Feb. 2020. Fig. 25 Starr, Forest and Kim. "Tamarindus indica (Tamarind). Pulp, Hawea Pl Olinda, Maui, Hawai'i." Starr Environmental, 120627-7639, 27 June 2012, (CC BY 4.0), www.starrenvironmental.com/images/image/?q=24558771243. Accessed 15 Feb. 2020. Fig. 26 Gunasena and Hughes. "Variation in dark red and brown pulp colour in tamarind." Fruits for the Future 1, Revised edition, Southampton Centre for Underutilised Crops, Southampton, UK, 2006, The National Archives, www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/webarchive. Accessed 20 Feb. 2020. Fig. 27,28 Kavitha, A., N., et al. "Tamarindus indica L., Indian date. Pulp, seeds." India Biodiversity Portal, 15 Mar. 2019, Biodiversity India, (CC BY-NC 3.0), indiabiodiversity.org/species/show/31829. Accessed 15 Feb. 2020. Fig. 29 Schmidt, Marco."Tamarind shelled pods." West African Plants, EOL, (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0), eol.org/pages/639027/media. Accessed 12 Feb. 2020. Fig. 30 Manjithkaini. "An emerging Tamarind tree seedling. Taken from Kerala, India." Commons Wikimedia, 3 May 2010, (CC BY-SA 3.0), commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:A_Tamarind_tree_seedling.jpg. Accessed 20 Feb. 2020. Fig. 32 Judgefloro. "Tamarind Tree." Enclyclopedia of Life, via Wikimedia Commons, 35062068, 30 Aug. 2014, EOL, (CC BY-SA 3.0), eol.org/pages/639027/media. Accessed 12 Feb. 2020. Fig. 33 Cutler, Wendy. "Tamarindus indica at Ala Moana Beach Park in Honolulu." Flickr, 24 Nov. 2014, (CC BY-SA 2.0), www.flickr.com/photos/wlcutler/23796397622/in/photostream/. Accessed 15 Feb. 2020. Fig. 34 Autan. "Giant tree of Tamarind Tamarindaus indica in Ayutaya, Thailand, May 1999." Flickr, 24 May 1999, (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0), www.flickr.com/photos/56119072@N00/240526038. Accessed 17 Feb. 2020. Fig. 36 Judgefloro. "The Marketplace Public Market Malolos Historic Town Center and Heritage District of Barangay Santo Rosario Caniogan." Commons Wikimedia, 20 Aug. 2017, (CC0), Image cropped, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Sampalok_(leaves_and_flowers)#/media/File:499The_Marketplace_Malolos_Public_Market_City_41.jpg. Accessed 20 Feb. 2020. Fig. 37 Talupu. "Tamarind rice - a popular rice dish from South India." Wikimedia Commons, 15 June 2015, (CC BY-SA 4.0), commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tamarind_Rice_(Puliyogare).jpg. Accessed 9 Apr. 2021. Fig. 38 Babithajcosta. "Horse gram Tamarind Gravy." Wikimedia Commons, 16 June 2013, (CC BY-SA 4.0), commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kollu_rasam.JPG. Accessed 9 Apr. 2021. Fig. 39 Torreblanca, German. "Tamarind candy pieces are wrapped in cellophane. They should be kept in the cupboard inside a plastic bag. It is a very spicy sweet." Wikimedia Commons, 2 Sept. 2016, (CC BY-SA 4.0), commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fiesta_de_las_Culturas_Indígenas_096.jpg. Accessed 28 Feb. 2020. Fig. 40 Mead, David E. "Tamarind (Tamarindus indica) pods and pulp for sale at a market in Baubau City, Buton Island, Indonesia." Commons Wikimedia, (CC0), commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Tamarindus_indica_(fruit)#/media/File:Tamarindepasta.jpg. Accessed 19 Feb. 2020. Fig. 41 Star, Erza. "Tamarindo De Playa." Cocktail Courier, www.cocktailcourier.com/cocktail/tamarindo-de-playa/. Accessed 28 Feb. 2020. Fig. 42 jonpenet. "Jamaican snack." Enclyclopedia of Life, via Wikimedia Commons, 11735418, 9 Oct. 2010, EOL, Public Domain, eol.org/pages/639027/media. Accessed 12 Feb. 2020. Fig. 43 Ganguly, Biswarup. " Photographed in Dhaka, Bangladesh." Wikimedia Commons, 31 May 2015, (CC BY 3.0), GFDL, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tamarind_and_Mango_Products_-_Kazi_Nazrul_Islam_Avenue_-_Dhaka_2015-05-31_2230.JPG. Accessed 9 Apr. 2021. Fig. 44 Mangosapiens. "A bowl of Salted Tamarind." Commons Wikimedia, 6 Sept. 2019, (CC BY-SA 4.0), commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Salted_Tamarind.jpg. Accessed 20 Feb. 2020. Fig. 45 Sanjay. "Balls of candy made from tamarind." Wikimedia Commons, 30 Dec. 2009, (CC BY-SA 3.0), GFDL, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tamarind_candy.jpg. Accessed 9 Apr. 2021. Fig. 46 Badhwar, Nitin. "Dahi Bhalla Chaat." Indian Food Series, 17 Sept. 2006, (CC BY-SA 2.0), commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Tamarind-based_food#/media/File:Bhalla_Papri_Chaat_with_saunth_chutney.jpg. Accessed 28 Feb. 2020. Fig. 47 Ferrara, Char. "Tamarind Shrimp, also known as Assam Prawns." Wok & Skillet, www.wokandskillet.com/tamarind-shrimp/. Accessed 28 Feb. 2020. Fig. 48 Carnalla, Andrés. "Agua de tamarindo." Mexican Food Journal, mexicanfoodjournal.com/tamarind-water/. Accessed 28 Feb. 2020. Fig. 49 Bernard, Roger. "Tamarindus indica L." Madagascar Catalogue Image Gallery, Missouri Botanical Garden, United States, Missouri, Bernard - 2453 - Madagascar, 27 Jan. 2016, Tropicos®, (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0), legacy.tropicos.org/Image/100519021. Accessed 12 Sept. 2019. Fig. 50 Friday, J. B. "Bowl made of tamarind wood by Scott Hare." Flickr, www.flickr.com/photos/55059208@N07/5267881987/in/photolist. Accessed 20 Feb. 2020. Fig. 51 Ganguly, Biswarup. "The 186th Annual Flower Show was held at the garden of the Agri-Horticultural Society of India." Commons Wikimedia, 10 Feb. 2013, GFDL, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tamarindus_indica_-_Bonsai_-_Alipore_-_Kolkata_2013-02-10_4671.JPG. Accessed 20 Feb. 2020. Fig. 52 Daderot. "Bonsai in the Morikami Museum and Japanese Gardens - Palm Beach County, Florida, USA." Commons Wikimedia, 24 Mar. 2017, (CC0 1.0), commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tamarindus_indica_-_Morikami_Museum_and_Japanese_Gardens_-_Palm_Beach_County,_Florida_-_DSC03480.jpg. Accessed 20 Feb. 2020. Fig. 53 Wunderlin, R. P., et al. "Tamarindus indica L." Atlas of Florida Plants, [S. M. Landry and K. N. Campbell (application development), USF Water Institute.] Institute for Systematic Botany, University of South Florida, Tampa, 2019, florida.plantatlas.usf.edu/Plant.aspx?id=1775. Accessed 12 Feb. 2020. Fig. 54 Takeaway. "Tamarind sold at a rural market near the village of Mae On, Chiang Mai province, Thailand." Commons Wikimedia, 17 Feb. 2010, (CC BY-SA 3.0), commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Tamarindus_indica_(fruit)#/media/File:Vatch_tamarind.jpg. Accessed 20 Feb. 2020. Fig. 55 Dunkel, Alex. "Ring-tailed lemur eating tamarind fruit, taken at America's Teaching Zoo at Moorpark College." Wikimedia Commons, 17 Jan. 2008, (CC BY 3.0), commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lemur_eating_tamarind.jpg. Accessed 10 Nov. 2020. * UF/IFAS Assessment of Non-native Plants in Florida's Natural Areas ** Information provided is not intended to be used as a guide for treatment of medical conditions. Published 28 Mar. 2020 LR. Last update 9 Apr. 2021 LR |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||