Article from

VSCNews, Vegetable and Specialty Crop News

by Alan Chambers

Potential for Commercial Vanilla Production in Southern Florida

Think about your favorite desserts like ice cream, cookies,

cream-filled pastries and chocolate. These indulgences are the perfect

end to an otherwise healthy meal, or a guilty snack when no one’s

looking. Many of our favorite desserts include a common, yet

irresistible, vanillin flavor extract from the “bean” of the vanilla

orchid. Vanillin has enhanced the sensory experience of many foods and

beverages for hundreds of years, and it’s hard to imagine a

contemporary diet without it.

Now imagine your favorite dessert

created with premium, natural vanillin from southern Florida growers

committed to quality, sustainability and the economic viability of

local agriculture. Growing vanilla in southern Florida may be a new

industry for ambitious entrepreneurs, but there are many factors

suggesting that this might be a successful venture.

VANILLA SPECIES

There are approximately 110 species of vanilla orchids, but only a few produce the aroma associated with vanilla extract. Vanilla planifolia

(commercial vanilla) is an emerald green, shade-loving vine native to

the Americas. It was most likely domesticated in southeastern Mexico by

Totonac or Mayan people, and was used by Aztec noble families to flavor

their chocolate drink. V. planifolia

requires warm temperatures, a rainy season and plenty of filtered

sunshine to produce an annual crop of seed pods commonly called “beans.”

Vanilla species other than V. planifolia could also be relevant to an industry in southern Florida. V. x tahitensis is a chance hybrid between V. planifolia and V. odorata,

and is also commercially important on a limited scale. V. pompona is

grown on a very limited scale for pharmaceutical and perfume

applications.

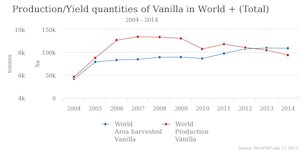

Fig. 1. World production of vanilla, 2004–2014

There are also four native vanilla species growing in southern Florida’s state parks and nature preserves. These include V. barbellata, V. phaeantha, V. dilloniana and V. mexicana.

These native species are certainly not an immediate solution for

commercial production, but their conservation and characterization

could provide useful genetics for a unique vanilla industry in southern

Florida. Native species can help uncover useful genetic traits

including adaptability to local environmental conditions, disease

resistance, and perhaps unique or enhanced fruit quality.

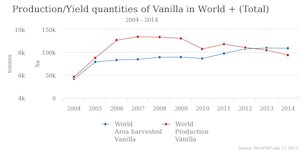

Fig. 2. Predicttion/yield quantities of Vanilla in World + (Total)

Unfortunately,

each native Florida orchid is currently endangered and at risk of being

lost before their true value is understood.

VANILLIN

Vanillin

is the world’s most popular spice, and one of the most expensive.

Natural vanillin extract is a premium flavoring and perfuming

ingredient with a presumably insatiable global demand. Approximately 15

million kilograms of vanillin were produced in 2010, worth around

$1,200 to $4,000 per kilogram, with less than 1 percent coming from

vanilla orchids.

A vanilla bean contains about 2 percent

vanillin, though the natural extract contains other components that

also contribute to its quality. Madagascar is regularly the highest

producer of orchid-based vanillin, followed by Indonesia, China and

Mexico. Indonesia, Papau New Guinea, China and Madagascar have the

highest gross production of seed pods (Fig. 1).

The United

States is one of the biggest importers of cured beans and exporters of

the finished product (vanillin extract), worth $26 million in 2004,

according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United

Nations. Supply is heavily influenced by environmental and biotic

factors leading to volatility in production and market prices, as shown

for global production from 2004 to 2014 (Fig. 2). Production volume,

quality and price are not equivalent across producing countries.

Demand

for vanillin flavoring from natural sources, including vanilla orchids,

is predicted to increase primarily from 1) growing consumption of

vanillin products including desserts like ice cream and chocolate, and

2) a trending force from major food companies investing in natural

ingredients. This suggests that demand could be increasing specifically

for premium vanillin flavoring from vanilla orchids. Vanilla

cultivation could be suitable for southern Florida based on a favorable

growing environment and high anticipated revenue generation.

CULTIVATION

Vanilla

cultivation requires specific infrastructure. First, vanilla orchids

require shade. Common nursery shade houses would be suitable. Shade has

also been provided by “tutor” trees, including citrus trees in some

countries. In these cases, vanilla cultivation acts as a revenue

generator while new tree plantings are getting established. Otherwise,

the vines require structural support from some other form of

trellising. Vanilla orchids do require an establishment period of a few

years prior to flowering, and research will be needed to optimize this

process for southern Florida.

The pods require thermal

treatments, curing, sweating, drying and extraction to produce the full

flavor of natural vanilla extract. Various postharvest practices are

employed globally and further optimization could increase production

and quality of the finished products. Optimal growth and plant

maintenance methods would therefore need to be established for southern

Florida.

Fig. 3. Manual pollination of Vanilla planifolia.

CURRENT CHALLENGES

V.

planifolia currently requires manual pollination in order to set pods

(Fig. 3). Many homeowners in southern Florida pollinate their own

vanilla orchids. The technique is not complicated, but labor is a major

expense for commercial production. Pollination is achieved using a

small stick to circumvent a physical barrier within the flower (the

rostellum) and introduce pollen onto the stigmatic surface. V. planifolia flowers must be pollinated the morning they open, before the flowers wither and drop off the vine.

The

major pathogens of vanilla are Fusarium oxysporum, Colletotrichum

vanillae and Puccinia sinamononea. Poor cultural practices can increase

disease severity, and cultural practices are therefore often the first

method to reduce disease impacts. Additional control methods might be

necessary for high-density production in southern Florida.

GENETICS AND BREEDING

There are few vanilla cultivars available for commercial production. V. planifolia

is vegetatively propagated and widely distributed, resulting in a lack

of genetic diversity in most commercial systems. This generally

increases the risk of potentially devastating disease epidemics like

growers are currently experiencing in citrus and banana.

Care

must also be taken to obtain virus-free stock material for establishing

a vanillery. These risks could be reduced through a systematic breeding

program focusing on yield, quality and sustainability with regular

improvements to elite cultivars.

Obtaining and increasing stock

material for a vanillery would be relatively straightforward.

Information for establishing and maintaining vanilla plants is also

available from multiple sources. A systematic breeding program could

additionally provide novel and useful cultivars to support a vanilla

industry in southern Florida. The availability of closely related

species could also provide a route to the creation of superior

cultivars, but only sparse information exists for validating this

approach.

V. x tahitensis

is one example of a chance seedling giving rise to a niche industry.

The few native Florida orchids may prove especially interesting,

because they can produce seed pods in their natural environments

without manual pollination. The mechanisms for this specific trait

would be worth study in the future.

CONCLUSION

Vanillin

is a timeless ingredient with increasing demand. Market trends suggest

that demand will especially increase for premium, natural vanillin.

High prices for natural vanillin extract could justify investment for

domestic production. The opportunity for vanilla production in southern

Florida might also justify conservation efforts for our native vanilla

species that could guide future breeding work. In summary, these

challenges and opportunities should resonate with many in our industry,

and are worth further consideration especially when enjoying your next

bowl of ice cream.

Alan Chambers is an assistant

professor at the University of Florida/Institute of Food and

Agricultural Sciences Tropical Research and Education Center in

Homestead

|

|