From the book

Fruits of Warm Climates

by Julia F. Morton

Lychee

Litchi chinensis Sonn.

Nephelium litchi Cambess

SAPINDACEAE

The lychee is the most renowned of a group of edible fruits of the soapberry family, Sapindaceae. It is botanically designated Litchi chinensis Sonn. (Nephelium litchi

Cambess) and widely known as litchi and regionally as lichi, lichee,

laichi, leechee or lychee. Professor G. Weidman Groff, an influential

authority of the recent past, urged the adoption of the latter as

approximating the pronunciation of the local name in Canton, China, the

leading center of lychee production. I am giving it preference here

because the spelling best indicates the desired pronunciation and helps

to standardize English usage. Spanish and Portuguese-speaking people

call the fruit lechia; the French, litchi, or, in French-speaking

Haiti, quenepe chinois, distinguishing it from the quenepe, genip or

mamoncillo of the West Indies, Melicoccus bijugatus, q.v. The German word is litschi.

Plate XXXII: LYCHEE, Litchi chinensis

Description

The

lychee tree is handsome, dense, round-topped, slow-growing, 30 to 100

ft (9-30 m) high and equally broad. Its evergreen leaves, 5 to 8 in

(12.5-20 cm) long, are pinnate, having 4 to 8 alternate,

elliptic-oblong to lanceolate, abruptly pointed, leaflets, somewhat

leathery, smooth, glossy, dark-green on the upper surface and

grayish-green beneath, and 2 to 3 in (5-7.5 cm) long. The tiny

petalless, greenish-white to yellowish flowers are borne in terminal

clusters to 30 in (75 cm) long. Showy fruits, in loose, pendent

clusters of 2 to 30 are usually strawberry-red, sometimes rose, pinkish

or amber, and some types tinged with green. Most are aromatic, oval,

heart-shaped or nearly round, about 1 in (2.5 cm) wide and 1 1/2 in (4

cm) long; have a thin, leathery, rough or minutely warty skin, flexible

and easily peeled when fresh. Immediately beneath the skin of some

varieties is a small amount of clear, delicious juice. The glossy,

succulent, thick, translucent-white to grayish or pinkish fleshy aril

which usually separates readily from the seed, suggests a large,

luscious grape. The flavor of the flesh is subacid and distinctive.

There is much variation in the size and form of the seed.

Normally,

it is oblong, up to 3/4 in (20 mm) long, hard, with a shiny, dark-brown

coat and is white internally. Through faulty pollination, many fruits

have shrunken, only partially developed seeds (called "chicken tongue")

and such fruits are prized because of the greater proportion of flesh.

In a few days, the fruit naturally dehydrates, the skin turns brown and

brittle and the flesh becomes dry, shriveled, dark-brown and

raisin-like, richer and somewhat musky in flavor. Because of the

firmness of the shell of the dried fruits, they came to be nicknamed

"lychee, or litchi, nuts" by the uninitiated and this erroneous name

has led to much misunderstanding of the nature of this highly desirable

fruit. It is definitely not a "nut", and the seed is inedible.

Origin and Distribution

The

lychee is native to low elevations of the provinces of Kwangtung and

Fukien in southern China, where it flourishes especially along rivers

and near the seacoast. It has a long and illustrious history having

been praised and pictured in Chinese literature from the earliest known

record in 1059 A.D. Cultivation spread over the years through

neighboring areas of southeastern Asia and offshore islands. Late in

the 17th Century, it was carried to Burma and, 100 years later, to

India. It arrived in the West Indies in 1775, was being planted in

greenhouses in England and France early in the 19th Century, and

Europeans took it to the East Indies. It reached Hawaii in 1873, and

Florida in 1883, and was conveyed from Florida to California in 1897.

It first fruited at Santa Barbara in 1914. In the 1920's, China's

annual crop was 30 million lbs (13.6 million kg). In 1937 (before WW

II) the crop of Fukien Province alone was over 35 million lbs (16

million kg). In time, India became second to China in lychee

production, total plantings covering about 30,000 acres (12,500 ha).

There are also extensive plantings in Pakistan, Bangladesh, Burma,

former Indochina, Taiwan, Japan, the Philippines, Queensland,

Madagascar, Brazil and South Africa. Lychees are grown mostly in

dooryards from northern Queensland to New South Wales, but commercial

orchards have been established in the past 20 years, some consisting of

5,000 trees.

Madagascar began experimental refrigerated

shipments of lychees to France in 1960. It is recorded that there were

2 trees about 6 years old in Natal, South Africa, in 1875. Others were

introduced from Mauritius in 1876. Layers from these latter trees were

distributed by the Durban Botanical Gardens and lychee-growing expanded

steadily until in 1947 there were 5,000 bearing trees on one estate and

5,000 newly planted on another property, a total of 40,000 in all.

In

Hawaii, there are many dooryard trees but commercial plantings are

small. The fruit appears on local markets and small quantities are

exported to the mainland but the lychee is too undependable to be

classed as a crop of serious economic potential there. Rather, it is

regarded as a combination ornamental and fruit tree.

There are

only a few scattered trees in the West Indies and Central America apart

from some groves in Cuba, Honduras and Guatemala. In California, the

lychee will grow and fruit only in protected locations and the climate

is generally too dry for it. There are a few very old trees and one

small commercial grove. In the early 1960's, interest in this crop was

renewed and some new plantings were being made on irrigated land.

At

first it was believed that the lychee was not well suited to Florida

because of the lack of winter dormancy, exposing successive flushes of

tender new growth to the occasional periods of low temperature from

December to March. The earliest plantings at Sanford and Oviedo were

killed by severe freezes. A step forward came with the importation of

young lychee trees from Fukien, China, by the Rev. W.M. Brewster

between 1903 and 1906. This cultivar, the centuries-old 'Chen-Tze' or

'Royal Chen Purple', renamed 'Brewster' in Florida, from the northern

limit of the lychee-growing area in China, withstands light frost and

proved to be very successful in the Lake Placid area–the "Ridge"

section of Central Florida.

Layered trees were available from

Reasoner's Royal Palm Nurseries in the early 1920's, and the Reasoner's

and the U.S. Department of Agriculture made many new introductions for

trial. But there were no large plantings until an improved method of

propagation was developed by Col. William R. Grove who became

acquainted with the lychee during military service in the Orient,

retired from the Army, made his home at Laurel (14 miles south of

Sarasota, Florida) and was encouraged by knowledgeable Prof. G. Weidman

Groff, who had spent 20 years at Canton Christian College. Col. Grove

made arrangements to air-layer hundreds of branches on some of the old,

flourishing 'Brewster' trees in Sebring and Babson Park and thus

acquired the stock to establish his lychee grove. He planted the first

tree in 1938, and by 1940 was selling lychee plants and promoting the

lychee as a commercial crop. Many small orchards were planted from

Merritt's Island to Homestead and the Florida Lychee Growers'

Association was founded in 1952, especially to organize cooperative

marketing. The spelling "lychee" was officially adopted by the

association upon the strong recommendation of Professor Groff.

In

1960, over 6,000 lbs (2,720 kg) were shipped to New York, 4,000 lbs

(1,814 kg) to California, nearly 6,000 lbs (2,720 kg) to Canada, and

3,900 lbs (1, 769 kg) were consumed in Florida, though this was far

from a record year. The commercial lychee crop in Florida has

fluctuated with weather conditions, being affected not only by freezes

but also by drought and strong winds. Production was greatly reduced in

1959, to a lesser extent in 1963, fell drastically in 1965, reached a

high of 50,770 lbs (22,727 kg) in 1970, and a low of 7,200 lbs (3,273

kg) in 1974. Some growers lost up to 70% of their crop because of

severe cold in the winter of 1979-80. Of course, there are many bearing

trees in home gardens that are not represented in production figures.

The fruit from these trees may be merely for household consumption or

may be purchased at the site by Chinese grocers or restaurant

operators, or sold at roadside stands.

Though the Florida lychee

industry is small, mainly because of weather hazards, irregular bearing

and labor of hand-harvesting, it has attracted much attention to the

crop and has contributed to the dissemination of planting material to

other areas of the Western Hemisphere. Escalating land values will

probably limit the expansion of lychee plantings in this rapidly

developing state. Another limiting factor is that much land suitable

for lychee culture is already devoted to citrus groves.

Varieties

Professor

Groff, in his book, The lychee and the lungan, tells us that the

production of superior types of lychee is a matter of great family

pride and local rivalry in China, where the fruit is esteemed as no

other. In 1492, a list of 40 lychee varieties, mostly named for

families, was published in the Annals of Fukien. In the Kwang provinces

there were 22 types, 30 were listed in the Annals of Kwangtung, and 70

were tallied as varieties of Ling Nam. The Chinese claim that the

lychee is highly variable under different cultural and soil conditions.

Professor Groff concluded that one could catalog 40 or 50 varieties as

recognized in Kwangtung, but there were only 15 distinct, widely-known

and commercial varieties grown in that province, half of them marketed

in season in the City of Canton. Some of these are classed as

"mountain" types; the majority are "water types" (grown in low,

well-irrigated land). There is a special distinction between the kinds

of lychee that leak juice when the skin is broken and those that retain

the juice within the flesh. The latter are called "dry- and -clean" and

are highly prized. There is much variation in form (round, egg-shaped

or heart-shaped), skin color and texture, the fragrance and flavor and

even the color, of the flesh; and the amount of "rag" in the seed

cavity; and, of prime importance, the size and form of the seed.

The following are the 15 cultivars recognized by Professor Groff:

'No Mai Tsze',

or 'No mi ts 'z' (glutinous rice) is the leading variety in China;

large, red, "dry-and-clean"; seeds often small and shriveled. It is one

of the best for drying, and is late in season. It does best when

grafted onto the 'Mountain' lychee.

'Kwa Iuk'

or 'Kua lu' (hanging green) is a famous lychee; large, red with a green

tip and a typical green line; "dry-and-clean"; of outstanding flavor

and fragrance. It was, in olden times, a special fruit for presentation

to high officials and other persons in positions of honor. Professor

Groff was given a single fruit in a little red box!

'Kwai mi'

or 'Kuei Wei', (cinnamon flavor) which came to be called 'Mauritius' is

smaller, heart-shaped, with rough red skin tinged with green on the

shoulders and usually having a thin line running around the fruit. The

seed is small and the flesh very sweet and fragrant. The branches of

the tree curve upward at the tips and the leaflets curl inward from the

midrib.

'Hsiang li', or

'Heung lai' (fragrant lychee) is home by a tree with distinctive erect

habit having upward-pointing leaves. The fruit is small, very rough and

prickly, deep-red, with the smallest seeds of all, and the flesh is of

superior flavor and fragrance. It is late in season. Those grown in Sin

Hsing are better than those grown in other locations.

'Hsi Chio tsu',

or 'Sai kok tsz' (rhinoceros horn) is borne by a large-growing tree.

The fruit is large, rough, broad at the base and narrow at the apex;

has somewhat tough and fibrous, but fragrant, sweet, flesh. It ripens

early.

'Hak ip', or 'Hei

yeh', (black leaf) is borne by a densely-branched tree with large,

pointed, slightly curled, dark-green leaflets. The fruit is medium-red,

sometimes with green tinges, broad-shouldered, with thin, soft skin and

the flesh, occasionally pinkish, is crisp and sweet. This is rated as

"one of the best 'water' lychees."

'Fei tsu hsiao',

or 'Fi tsz siu' (imperial concubine's laugh, or smile) is large,

amber-colored, thin-skinned, with very sweet, very fragrant flesh.

Seeds vary from large to very small. It ripens early.

'T' ang po',

or 'T' ong pok' (pond embankment) is from a small-leaved tree. The

fruit is small, red, rough, with thin, juicy acid flesh and very little

rag. It is a very early variety.

'Sheung shu wai'

or'Shang hou huai', (President of a Board's embrace) is borne on a

small-leaved tree. The fruit is large, rounded, red, with many dark

spots. It has sweet flesh with little scent and the seed size is

variable. It is rather late in season.

'Ch'u ma lsu',

or 'Chu ma lsz' (China grass fiber) has distinctive, lush foliage. The

leaves are large, overlapping, with long petioles. The fruits are large

with prominent shoulders and rough skin, deep red inside. While very

fragrant, the flesh is of inferior flavor and clings to the seed which

varies from large to small.

'Ta tsao',

or 'Tai tso' (large crop) is widely grown around Canton; somewhat

egg-shaped; skin rough, bright-red with many small, dense dots; flesh

firm, crisp, sweet, faintly streaked with yellow near the large seed.

The juice leaks when the skin is broken. The fruit ripens early.

'Huai chih',

or 'Wai chi' (the Wai River lychee) has medium-sized, blunt leaves. The

fruit is round with medium-smooth skin, a rich red outside, pink

inside; and leaking juice. This is not a high class variety but the

most commonly grown, high yielding, and late in season.

'San yueh hung',

or 'Sam ut hung' (third month red), also called 'Ma yuen', 'Ma un',

'Tsao kuo', 'Tso kwo', 'Tsao li', or 'Tsoli' (early lychee) is grown

along dykes. The branches are brittle and break readily; the leaves are

long, pointed, and thick. The fruit is very large, with red, thick,

tough skin and thick, medium-sweet flesh with much rag. The seeds are

long but aborted. This variety is popular mainly because it comes into

season very early.

'Pai la li chih',

or 'Pak lap lai chi' (white wax lychee), also called 'Po le tzu', or

'Pak lik tsz (white fragrant plant), is large, pink, rough, with

pinkish, fibrous, not very sweet flesh and large seeds. It ripens very

late, after 'Huai chih'.

'Shan chi',

or 'Shan chih' (mountain lychee), also called 'Suan chih', or 'Sun chi'

(sour lychee) grows wild in the hills and is often planted as a

rootstock for better varieties. The tree is of erect habit with erect

twigs and large, pointed, short-petioled leaves. The fruit is

bright-red, elongated, very rough, with thin flesh, acid flavor and

large seed.

'T'im ngam',

or 'T'ien yeh' (sweet cliff) is a common variety of lychee which

Professor Groff reported to be quite widely grown in Kwantung, but not

really on a commercial basis.

In his book, The Litchi, Dr. Lal

Behari Singh wrote that Bihar is the center of lychee culture in India,

producing 33 selected varieties classified into 15 groups. His

extremely detailed descriptions of the 10 cultivars recommended for

large-scale cultivation I have abbreviated (with a few bracketed

additions from other sources):

'Early Seedless',

or 'Early Bedana'. Fruit 1 1/3 in (3.4 cm) long, heart-shaped to oval;

rough, red, with green interspaces; skin firm and leathery; flesh

[ivory] to white, soft, sweet; seed shrunken, like a dog's tooth. Of

good quality. The tree bears a moderate crop, early in season.

'Rose-scented'.

Fruit 1 1/4 in (3.2 cm) long; rounded-heart-shaped; slightly rough,

purplish-rose, slightly firm skin; flesh gray-white, soft, very sweet.

Seed round-ovate, fully developed. Of good quality. [Tree bears a

moderate crop] in midseason.

'Early Large Red'.

Fruit slightly more than 1 1/3 in (3.4 cm) long, usually obliquely

heart-shaped; crimson [to carmine], with green interspaces; very rough;

skin very firm and leathery, adhering slightly to the flesh. Flesh

grayish-white, firm, sweet and flavorful. Of very good quality. [Tree

is a moderate bearer], early in season.

'Dehra Dun',

[or 'Dehra Dhun']. Fruit less than 1 1/2 in (4 cm) long; obliquely

heart-shaped to conical; a blend of red and orange-red; skin rough,

leathery; flesh gray-white, soft, of good, sweet flavor. Seed often

shrunken, occasionally very small. Of good quality; midseason. [This is

grown extensively in Uttar Pradesh and is the most satisfactory lychee

in Pakistan.]

'Late Long Red',

or 'Muzaffarpur'. Fruit less than 1 1/2 in (4 cm) long; usually

oblong-conical; dark-red with greenish interspaces; skin rough, firm

and leathery, slightly adhering to the flesh; flesh grayish-white,

soft, of good, sweet flavor. Seed cylindrical, fully developed. Of good

quality. [Tree is a heavy bearer], late in season.

'Pyazi'.

Fruit 1 1/3 in (3.4 cm) long; oblong-conical to heart-shaped; a blend

of orange and orange-red, with yellowish-red, not very prominent,

tubercles. Skin leathery, adhering; flesh gray-white, firm, slightly

sweet, with flavor reminiscent of "boiled onion". Seed cylindrical,

fully developed. Of poor quality. Early in season.

'Extra Early Green'.

Fruit 1 1/4 in (3.2 cm) long; mostly heart-shaped, rarely rounded or

oblong; yellowish-red with green interspaces; skin slightly rough,

leathery, slightly adhering; flesh creamy-white, [firm, of good,

slightly acid flavor]; seed oblong, cylindrical or flat. Of indifferent

quality. Very early in season.

'Kalkattia',

['Calcuttia', or 'Calcutta']. Fruit 1 1/2 in (4 cm) long; oblong or

lopsided; rose-red with darker tubercles; skin very rough, leathery,

slightly adhering; flesh grayish ivory, firm, of very sweet, good

flavor. Seed oblong or concave. Of very good quality. [A heavy bearer;

withstands hot winds]. Very late in season.

'Gulabi'.

Fruit 1 1/3 in (3.4 cm) long; heart-shaped, oval or oblong; pink-red to

carmine with orange-red tubercles; skin very rough, leathery,

non-adherent; flesh gray-white, firm, of good subacid flavor; seed

oblong-cylindrical, fully developed. Of very good quality. Late in

season.

'Late Seedless',

or 'Late Bedana'. Fruit less than 1 3/8 in (3.65 cm) long; mainly

conical, rarely ovate; orange-red to carmine with blackish-brown

tubercles; skin rough, firm, non-adherent; flesh creamy-white, soft;

very sweet, of very good flavor except for slight bitterness near the

seed. Seed slightly spindle-shaped, or like a dog's tooth;

underdeveloped. Of very good quality. [Tree bears heavily. Withstands

hot winds.] Late in season.

There are numerous lychee orchards in the submontane region of the Punjab. The leading variety is:

'Panjore common'.

Fruit is large, heart-shaped, deep-orange to pink; skin is rough, very

thin, apt to split. Tree bears heavily and has the longest fruiting

season-for an entire month beginning near the end of May. Six other

varieties commonly grown there are: 'Rose-scented', 'Bhadwari',

'Seedless No. 1', 'Seedless No. 2', 'Dehra Dun', and 'Kalkattia'.

In

South Africa, only one variety is produced commercially. It is the

'Kwai Mi' but it is locally called 'Mauritius' because nearly all of

the trees are descendants of those brought in from that island. In

South Africa, the fruit is of medium size, nearly round but slightly

oval, reddish-brown. Flesh is firm, of good quality and usually

contains a medium-sized seed, but certain fruits with broad, flat

shoulders and shortened form tend to have "chicken-tongue" seeds.

There

have been many other introductions into South Africa from China and

India but most failed to survive. In 1928, 16 varieties from India were

planted at Lowe's Orchards, Southport, Natal, but the records were lost

and they remained unnamed. A Litchi Variety Orchard of 26 cultivars

from India, China, Taiwan and elsewhere was established at the

Subtropical Horticulture Research Station in Nelspruit. Tentative

classifications grouped these into 3 distinct types–'Kwai Mi'

['Mauritius'], 'Hak Ip' (of high quality and small seed but a shy

bearer in the Low-veld), and the 'Madras', a heavy bearer of choice

fruits, bright-red, very rough, and with large seeds, but very sweet,

luscious flesh.

The first lychee introduced into Hawaii was the

'Kwai Mi', as was the second introduction several years later. The high

quality of this variety (sometimes locally called 'Charlie Long')

caused the lychee to become extremely popular and widely planted. The

Hawaiian Agricultural Experiment Station imported 3 'Brewster' trees in

1907, and various efforts were made to bring other types from China but

not all survived. A total of 16 varieties became well established in

Hawaii, including 'Hak Ip' which has become second to 'Kwai Mi' in

importance.

In

1942, the Agricultural Experiment Station set out a collection of 500

seedlings of 'Kwai Mi', 'Hak Ip' and 'Brewster' with a view to

selecting the trees showing the best performance. One tree of

outstanding character (a seedling of 'Hak Ip') was first designated

H.A.E.S. Selection 1-18-3 and was given the name 'Groff' in 1953. It is

a consistent bearer, late in season. The fruit is of medium size, dark

rose-red with green or yellowish tinges on the apex of each tubercle.

The flesh is white and firm; there is no leaking juice; the flavor is

excellent, sweet and subacid; most of the fruits have abortive,

"chicken-tongue" seeds and, accordingly have 20% more flesh than if the

seeds were fully developed.

'No Mai Tsze'

has been growing in Hawaii for over 40 years but has produced very few

fruits. 'Pat Po Heung' (eight precious fragrances), erroneously called

'Pat Po Hung' (eight precious red), somewhat resembles 'No Mai Tsze'

but is smaller; the skin is purplish-red, thin and pliable; the juice

leaks when the skin is broken; the flesh is soft, juicy, sweet even

when slightly unripe; the seed varies from medium to large. The tree is

slow-growing and of weak, spreading habit; it bears well in Hawaii.

Nevertheless, it is not commonly planted.

'Kaimana',

or 'Poamoho', an open-pollinated seedling of 'Hak Ip', developed by Dr.

R.A. Hamilton at the Poamoho Experiment Station of the University of

Hawaii, was released in 1982. The fruit resembled 'Kwai Mi' but is

twice as large, deep-red, of high quality, and the tree is a regular

bearer.

'Brewster' is

large, conical or wedge-shaped, red, with soft flesh, more acid than

that of 'Kwai mi', and the seeds are very often fully formed and large.

The leaflets are flat with slightly recurved margins and taper to a

sharp point.

There were many other introductions of seeds,

seedlings, cuttings or air-layers into the United States, from 1902 to

1924, mostly from China; also from India and Hawaii, and a few from

Java, Cuba, and Trinidad; and these were distributed to experimenters

in Florida and California, and some to botanical gardens in other

states, and to Cuba, Puerto Rico, Panama, Honduras, Costa Rica and

Brazil. Many were killed by cold weather in California and Florida.

In

1908, the United States Department of Agriculture brought in 27 plants

of 'Kwai mi'. At the same time, 20 plants of 'Hak Ip' were imported and

these were sent to George B. Cellon in Miami in 1918. A tree of the

'Bedana' was introduced from India in 1913. In 1920, Professor Groff

obtained seedlings of 'Shan Chi' (mountain lychee) from Kwantung

Province, together with air-layers of 'Sheung shu wai', 'No mai ts 'z',

and 'T' im ngam' (sweet cliff). The latter was found to bear more

regularly than 'Brewster' but exhibited nutritional deficiencies in

limestone soil.

Most of the various plants and rooted cuttings

from them were distributed for trial; the rest were kept in U.S.

Department of Agriculture greenhouses in Maryland.

'Bengal'–In

1929, the U.S. Department of Agriculture received a small lychee plant,

supposedly a seedling of 'Rose-scented', from Calcutta. It was planted

at the Plant Introduction Station in Miami and began bearing in 1940.

The fruits resembled 'Brewster' but were more elongated, were home in

large clusters, and the flesh was firm, not leaking juice when peeled.

All the fruits had fully developed seeds but smaller in proportion to

flesh than those of 'Brewster'. The habit of the tree is more spreading

than that of 'Brewster'; it has larger, more leathery, darker green

leave's, and the bark is smoother and paler. The original tree and its

air-layered progeny have shown no chlorosis on limestone in contrast to

'Brewster' trees growing nearby.

'Peerless',

believed to be a seedling of 'Brewster', originated at the Royal Palm

Nursery at Oneco; was transplanted to the T.R. Palmer Estate in

Belleair where C.E. Ware noticed from 1936 to 1938 that it bore fruit

of larger size, brighter color and higher percentage of abortive seed

than 'Brewster'. In 1938, Ware air-layered and removed 200 branches,

purchased the tree and moved it to his property in Clearwater. It

resumed fruiting in 1940 and annual crops recorded to 1956 showed good

productivity-averaging 383.4 lbs (174 kg) per year, and the rate of

abortive seeds ranged from 62% to 85%. The 200 air-layers were planted

out by Ware in 1942 and began bearing in 1946. Most of the fruits had

fully developed seeds but the rate of abortive seeds increased year by

year and in 1950 was 61% to 70%. The cultivar was named with the

approval of the Florida Lychee Growers Association. Two seedling

selections by Col. Grove, 'Yellow Red' and 'Late Globe', Prof. Groff

believed to be natural hybrids of 'Brewster' ´ 'Mountain'.

In

northern Queensland, 'Kwai Mi' is the earliest cultivar grown, and

about 10% of the fruits have "chicken tongue" seeds. 'Brewster' bears

in mid-season and is important though the seed is nearly always fully

formed and large. 'Hak Ip' is also midseason and large-seeded there.

'Bedana' is grown only in home gardens and the fruits have large seeds

unlike the usual "chicken tongue" seeds of the fruits of this cultivar

borne in India.

'Wai Chi'

is late in season (December), has small, round fruits, basically yellow

overlaid with red; the seed is small and oval. The tree is very compact

with upright branches, and prefers a cooler climate than that of

coastal north Queensland where it does not fruit heavily. The leaflets

are concave like those of 'Kwai Mi'.

A very similar, perhaps

identical, cultivar called 'Hong Kong' is grown in South Queensland.

'No Mai' bears poorly in Queensland and seems better adapted to cooler

areas.

Blooming and Pollination

There

are 3 types of flowers appearing in irregular sequence or, at times,

simultaneously, in the lychee inflorescence: a) male; b) hermaphrodite,

fruiting as female (about 30% of the total); c) hermaphrodite fruiting

as male. The latter tend to possess the most viable pollen. Many of the

flowers have defective pollen and this fact probably is the main cause

of the abortive seeds and also the common problem of shedding of young

fruits. The flowers require transfer of pollen by insects.

In

India, L.B. Singh recorded 11 species of bees, flies, wasps and other

insects as visiting lychee flowers for nectar. But honeybees, mostly Apis cerana indica, A. dorsata and A. florea, constitute 78% of the lychee-pollinating insects and they work the flowers for pollen and nectar from sunrise to sundown. A. cerana is the only hive bee and is essential in commercial orchards for maximum fruit production.

A

6-week survey in Florida revealed 27 species of lychee-flower visitors,

representing 6 different insect Orders. Most abundant, morning and

afternoon, was the secondary screw-worm fly (Callitroga macellaria), an undesirable pest. Next was the imported honeybee (Apis mellifera)

seeking nectar daily but only during the morning and apparently not

interested in the pollen. No wild bees were seen on the lychee flowers,

though wild bees were found in large numbers collecting pollen in an

adjacent fruit-tree planting a few weeks later. Third in order, but not

abundant, was the soldier beetle (Chauliognathus marginatus).

The rest of the insect visitors were present only in insignificant

number. Maintenance of bee hives in Florida lychee groves is necessary

to enhance fruit set and development. The fruits mature 2 months after

flowering.

In India and Hawaii, there has been some interest in

possible cross-breeding of the lychee and pollen storage tests have

been conducted. Lychee pollen has remained viable at room temperature

for 10 to 30 days in petri dishes; for 3 to 5 months in desiccators; 15

months at 32° F (0° C) and 25% relative humidity in

desiccators; and 31 months under deep-freeze, -9.4° F (-23° C).

There is considerable variation in the germination rates of pollen from

different cultivars. In India, 'Rose Scented' has shown mean viability

of 61.99% compared with 42.52% in 'Khattl'.

Climate

Groff

provided a clear view of the climatic requirements of the lychee. He

said that it thrives best in regions "not subject to heavy frost but

cool and dry enough in the winter months to provide a period of rest."

In China and India, it is grown between 15° and 30° N. "The

Canton delta ... is crossed by the Tropic of Cancer and is a

subtropical area of considerable range in climate. Great fluctuations

of temperature are common throughout the fall and winter months. In the

winter sudden rises of temperature will at times cause the lychee ...

to flush forth ... new growth. This new growth is seldom subject to a

freeze about Canton. On the higher elevations of the mountain regions

which are subject to frost the lychee is seldom grown . . . The more

hardy mountainous types of the lychee are very sour and those grown

near salt water are said to be likewise. The lychee thrives best on the

lower plains where the summer months are hot and wet and the winter

months are dry and cool."

Heavy frosts will kill young trees but

mature trees can withstand light frosts. Cold tolerance of the lychee

is intermediate between that of the sweet orange on one hand and mango

and avocado on the other. Location, land slope, and proximity to bodies

of water can make a great difference in degree of damage by freezing

weather. In the severe low temperature crisis during the winter of

1957-58, the effects ranged from minimal to total throughout central

and southern Florida. A grove of 12-to 14-year-old trees south of

Sanford was killed back nearly to the ground; on Merritt Island trees

of the same age were virtually undamaged, while a commercial mango

planting was totally destroyed. L.B. Singh resists the common belief

that the lychee needs winter cold spells that provide periods of

temperature between 30° and 40° F (-1.11° and 4.44° C)

because it does well in Mauritius where the temperature is never below

40° F (-1.11° C). However, lychee trees in Panama, Jamaica, and

other tropical areas set fruit only occasionally or not at all.

Heavy

rain or fog during the flowering period is detrimental, as are hot,

dry, strong winds which cause shedding of flowers, also splitting of

the fruit skin. Splitting occurs, too, during spells of alternating

rain and hot, dry periods, especially on the sunny side of the tree.

Spraying with Ethephon at 10 ppm reduced splitting in 'Early Large Red'

in experiments in Nepal.

Soil

The

lychee grows well on a wide range of soils. In China it is cultivated

in sandy or clayey loam, "river mud", moist sandy clay, and even heavy

clay. The pH should be between 6 and 7. If the soil is deficient in

lime, this must be added. However, in an early experiment in a

greenhouse in Washington, D.C., seedlings planted in acid soil showed

superior growth and the roots had many nodules filled with mycorrhizal

fungi. This caused some to speculate that inoculation might be

desirable. Later, in Florida, profuse nodulation was observed on roots

of lychee seedlings that had not been inoculated but merely grown in

pots of sphagnum moss and given a well-balanced nutrient solution.

The

lychee attains maximum growth and productivity on deep alluvial loam

but flourishes in extreme southern Florida on oolitic limestone

providing it is put in an adequate hole and irrigated in dry seasons.

The

Chinese often plant the lychee on the banks of ponds and streams. In

low, wet land, they dig ditches 10 to 15 ft (3-4.5 m) wide and 30 to 40

ft (9-12 m) apart, using the excavated soil to form raised beds on

which they plant lychee trees, so that they have perfect drainage but

the soil is always moist. Though the lychee has a high water

requirement, it cannot stand water-logging. The water table should be

at least 4 to 6 ft (1.2-1.8 m) below the surface and the underground

water should be moving inasmuch as stagnant water induces root rot. The

lychee can stand occasionally brief flooding better than citrus. It

will not thrive under saline conditions.

Propagation

Lychees

do not reproduce faithfully from seed, and the choicest have abortive,

not viable, seed. Furthermore, lychee seeds remain viable only 4 to 5

days, and seedling trees will not bear until they are 5 to 12, or even

25, years old. For these reasons, seeds are planted mostly for

selection and breeding purposes or for rootstock.

Attempts to

grow the lychee from cuttings have been generally discouraging, though

80% success has been claimed with spring cuttings in full sun, under

constant mist and given weekly liquid nutrients. Ground-layering has

been practiced to some extent. In China, air-layering (marcotting, or

gootee) is the most popular means of propagation and has been practiced

for ages. By their method, a branch of a chosen tree is girdled,

allowed to callus for 1 to 2 days and then is enclosed in a ball of

sticky mud mixed with chopped straw or dry leaves and wrapped with

burlap. With frequent watering, roots develop in the mud and, in about

100 days, the branch is cut off, the ball of earth is increased to

about 12 in (30 cm) in width, and the air-layer is kept in a sheltered

nursery for a little over a year, then gradually exposed to full sun

before it is set out in the orchard. Some air-layers are planted in

large clay pots and grown as ornamentals.

The Chinese method of

air-layering has many variations. In fact, 92 modifications have been

recorded and experimented with in Hawaii. Inarching is also an ancient

custom, selected cultivars being joined to 'Mountain' lychee rootstock.

In

order to make air-layering less labor-intensive, to eliminate the

watering, and also to produce portable, shippable layers, Colonel

Grove, after much experimentation, developed the technique of packing

the girdle with wet sphagnum moss and soil, wrapping it in

moisture-proof clear plastic that permits exchange of air and gasses,

and tightly securing it above and below. In about 6 weeks, sufficient

roots are formed to permit detaching of the layer, removal of the

plastic wrap, and planting in soil in nursery containers. It is

possible to air-layer branches up to 4 in (10 cm) thick, and to take

200 to 300 layers from a large tree.

Studies in Mexico have led

to the conclusion that, for maximum root formation, branches to be

air-layered should not be less than 5/8 in (15 mm) in diameter, and, to

avoid undue defoliation of the parent tree, should not exceed 3/4 in

(20 mm). The branches, of any age, around the periphery of the canopy

and exposed to the sun, make better air-layers with greater root

development than branches taken from shaded positions on the tree. The

application of growth regulators, at various rates, has shown no

significant effect on root development in the Mexican experiments. In

India, certain of the various auxins tried stimulated root formation,

forced early maturity of the layers, but contributed to high mortality.

South African horticulturists believe that tying the branch up so that

it is nearly vertical induces vigorous rooting.

The

new trees, with about half of the top trimmed off and supported by

stakes, are kept in a shade house for 6 weeks before setting out.

Improvements in Colonel Grove's system later included the use of

constant mist in the shade house. Also, it was found that birds pecked

at the young roots showing through the transparent wrapping, made holes

in the plastic and caused dehydration. It became necessary to shield

the air-layers with a cylinder of newspaper or aluminum foil. As time

went on, some people switched to foil in place of plastic for wrapping

the air-layers.

The air-layered trees will fruit in 2 to 5 years

after planting, Professor Groff said that a lychee tree is not in its

prime until it is 20 to 40 years old; will continue bearing a good crop

for 100 years or longer. One disadvantage of air-layering is that the

resultant trees have weak root systems. In China, a crude method of

cleft-grafting has long been employed for special purposes, but,

generally speaking, the lychee has been considered very difficult to

graft. Bark, tongue, cleft, and side-veneer grafting, also chip-and

shield-budding, have been tried by various experimenters in Florida,

Hawaii, South Africa and elsewhere with varing degrees of success. The

lychee is peculiar in that the entire cambium is active only during the

earliest phases of secondary growth. The use of very young rootstocks,

only 1/4 in (6 mm) in diameter and wrapping the union with strips of

vinyl plastic film, have given good results. A 70% success rate has

been achieved in splice-grafting in South Africa. Hardened-off, not

terminal, wood of young branches 1/4 in (6 mm) thick is first ringed

and the bark-ring removed. After a delay of 21 days, the branch is cut

off at the ring, defoliated but leaving the base of each petiole, then

a slanting cut is made in the rootstock 1 ft (30 cm) above the soil, at

the point where it matches the thickness of the graftwood (scion), and

retaining as many leaves as possible. The cut is trimmed to a perfectly

smooth surface 1 in (2.5 cm) long; the scion is then trimmed to 4 in

(10 cm) long, making a slanting cut to match that on the rootstock. The

scion should have 2 slightly swollen buds. After joining the scion and

the rootstock, the union is wrapped with plastic grafting tape and the

scion is completely covered with grafting strips to prevent

dehydration. In 6 weeks the buds begin to swell, and the plastic is

slit just above the bud to permit sprouting. When the new growth has

hardened off, all the grafting tape is removed. The grafting is

performed in a moist, warm atmosphere. The grafted plants are

maintained in containers for 2 years or more before planting out, and

they develop strong taproots.

In India, a more recent

development is propagation by stooling, which has been found "simpler,

quicker and more economical" there than air-layering. First, air-layers

from superior trees are planted 4 ft (1.2 m) apart in "stool beds"

where enriched holes have been prepared and left open for 2 weeks.

Fertilizer is applied when planting (at the beginning of September) and

the air-layers are well established by mid-October and putting out new

flushes of growth in November. Fertilizer is applied again in

February-March and June-July. Shallow cultivation is performed to keep

the plot weed-free. At the end of 2 1/2 years, in mid-February, the

plants are cut back to 10 in (25 cm) from the ground. New shoots from

the trunk are allowed to grow for 4 months. In mid-June, a ring of bark

is removed from all shoots except one on each plant and lanolin paste

containing IBA (2,500 ppm) is applied to the upper portion of the

ringed area. Ten days later, earth is heaped up to cover 4 to 6 in

(10-15 cm) of the stem above the ring. This causes the shoots to root

profusely in 2 months. The rooted shoots are separated from the plant

and are immediately planted in nursery beds or pots. Those which do not

wilt in 3 weeks are judged suitable for setting out in the field. The

earth around the parent plants is leveled and the process of

fertilization, cultivation, ringing and earthing-up and harvesting of

stools is repeated over and over for years until the parent plants have

lost their vitality. It is reported that the transplanted shoots have a

survival rate of 81-82% as compared with 40% to 50% in air-layers.

Culture

Spacing:

For a permanent orchard, the trees are best spaced 40 ft (12 m) apart

each way. In India, a 30 ft spacing is considered adequate, probably

because the drier climate limits the overall growth. Portions of the

tree shaded by other trees will not bear fruit. For maximum

productivity, there must be full exposure to light on all sides.

In

the Cook Islands, the trees are planted on a 40 x 20 ft (12 x 6 m)

spacing–56 trees per acre (134 per ha)–but in the 15th

year, the plantation is thinned to 40 x 40 ft (12 x l2 m).

Wind protection:

Young trees benefit greatly by wind protection. This can be provided by

placing stakes around each small tree and stretching cloth around them

as a windscreen. In very windy locations, the entire plantation may be

protected by trees planted as windbreaks but these should not be so

close as to shade the lychees. The lychee tree is structurally highly

wind-resistant, having withstood typhoons, but shelter may be needed to

safeguard the crop. During dry, hot months, lychee trees of any age

will benefit from overhead sprinkling; they are seriously retarded by

water stress.

Fertilization

Newly planted trees must be watered but not fertilized beyond the

enrichment of the hole well in advance of planting. In China, lychee

trees are fertilized only twice a year and only organic material is

used, principally night soil, sometimes with the addition of soybean or

peanut residue after oil extraction, or mud from canals and fish ponds.

There is no great emphasis on fertilization in India. It has been

established that a harvest of 1,000 lbs (454.5 kg) removes

approximately 3 lbs (1,361 g) K2O, 1 lb (454 g) P2O5, 1 lb (454 g) N,

3/4 lb (340 g) CaO, and 1/2 lb (228 g) MgO from the soil. It is judged,

therefore, that applications of potash, phosphate, lime and magnesium

should be made to restore these elements.

Fertilizer experiments

on fine sand in central Florida have shown that medium rates of N

(either sulfate of ammonia or ammonium nitrate), P2O5, K2O, and MgO,

together with one application of dolomite limestone at 2 tons/acre (4.8

tons/ha) are beneficial in counteracting chlorosis and promoting

growth, flowering and fruit-set and reducing early fruit shedding.

Excessive use of nitrogen suppresses growth and interferes with the

uptake of other nutrients. If vegetative dormancy is to be encouraged

in bearing trees, fertilizer should be withheld in fall and early

winter.

In limestone soil, it may be necessary to spread

chelated iron 2 or 3 times a year to avoid chlorosis. Zinc deficiency

is evidenced by bronzing of the leaves. It is corrected by a foliar

spray of 8 lbs (3.5 kg) zinc sulphate and 4 lbs (1.8 kg) hydrated lime

in 48 qts (45 liters) of water. Because of the very shallow root system

of the lychee, a surface mulch is very beneficial in hot weather.

Pruning

Ordinarily, the tree is not pruned after the judicious shaping of the

young plant, because the clipping off of a branch tip with each cluster

of fruits is sufficient to promote new growth for the next crop. Severe

pruning of old trees may be done to increase fruit size and yield for

at least a few years.

Girdling

The Indian farmer may girdle the

branches or trunk of his lychee trees in September to enhance flowering

and fruiting. Tests on 'Brewster' in Hawaii confirmed the much higher

yield obtained from branches girdled in September. Girdling of trees

that begin to flush in October and November is ineffective. Similar

trials in Florida showed increased yield of trees that had poor crops

the previous year, but there was no significant increase in trees that

had been heavy bearers. Furthermore, many branches were weakened or

killed by girdling. Repeated girdling as a regular practice would

probably seriously interfere with overall growth and productivity.

Indian

horticulturists warn that girdling in alternate years, or girdling just

half of the tree, may be preferable to annual girdling and that, in any

case, heavy fertilization and irrigation should precede girdling. Fall

spraying of growth inhibitors has not been found to increase yields.

Harvesting

For

home use or for local markets, lychees are harvested when fully

colored; for shipment, when only partly colored. The final swelling of

the fruit causes the protuberances on the skin to be less crowded and

to slightly flatten out, thus an experienced picker will recognize the

stage of full maturity. The fruits are rarely picked singly except for

immediate eating out-of-hand, because the stem does not normally detach

without breaking the skin and that causes the fruit to spoil quickly.

The clusters are usually clipped with a portion of stem and a few

leaves attached to prolong freshness. Individual fruits are later

clipped from the cluster leaving a stub of stem attached. Harvesting

may need to be done every 3 to 4 days over a period of 3-4 weeks. It is

never done right after rain, as the wet fruit is very perishable. The

lychee tree is not very suitable for the use of ladders. High clusters

are usually harvested by metal or bamboo pruning poles. A worker can

harvest 55 lbs (25 kg) of fruits per hour.

Yield

The

yield varies with the cultivar, age, weather, presence of pollinators,

and cultural practices. In India, a 5-year-old tree may produce 500

fruits, a 20-year-old tree 4,000 to 5,000 fruits–160 to 330 lbs

(72.5-149.6 kg). Exceptional trees have borne 1,000 lbs (455 kg) of

fruit per year. One tree in Florida has borne 1,200 lbs (544 kg). In

China, there are reports of 1,500 lb crops (680 kg). In South Africa,

trees 25 years old have averaged 600 lbs (272 kg) each in good years;

and an average yield per acre is approximately 10,000 lbs annually

(roughly equivalent to 10,000 kg per hectare).

Keeping Quality, Storage and Shipping

Freshly

picked lychees keep their color and quality only 3 to 5 days at room

temperature. If pre-treated with 0.5% copper sulphate solution and kept

in perforated polyethylene bags, they will remain fresh somewhat longer.

Fresh

fruits, picked individually by snapping the stems and later de-stemmed

during grading, and packed in shallow, ventilated cartons with

shredded-paper cushioning, have been successfully shipped by air from

Florida to markets throughout the United States and also to Canada. In

South Africa, freshly picked lychees have been placed on trays in

ventilated sheds, dusted with sulphur and left overnight, and then

allowed to "wilt" in lugs for 24 to 48 hours to permit any infested or

injured fruits to become conspicuous before grading and packing. It is

said that fruits so treated retain their fresh color and are unaffected

by fungi or pests for several weeks.

In China and India, lychees

are packed in baskets or crates lined with leaves or other cushioning.

The clusters or loose fruits are best packed in trays with protective

sheets between the layers and no more than 5 single layers or 3 double

layers are joined together. The pack should not be too tight.

Containers for stacked trays or fruits not so arranged, must be fairly

shallow to avoid too much weight and crushing. Spoilage may be retarded

by moistening the fruits with a salt solution.

In the Cook

Islands, the fruits are removed from the clusters, dipped in Benlate to

control fungal growth, dried on racks, then packed in cartons for

shipment to New Zealand. South African shippers immerse the fruits for

10 minutes in a suspension of 0.375 dicloran 50% wp plus 0.625 g

benomyl 50% wp per liter of water warmed to 125.6º F (52º C).

Tests at CSIRO, Div. of Food Research, New South Wales, Australia, in

1982, showed good color retention, retardation of weight loss and

fungal spoilage in lychees dipped in hot benomyl 0.05% at 125.6º F

(52º C) for two minutes and packed in trays with PVC "skrink" film

covering. The chemical treatment had not yet been approved by health

authorities.

Lychee clusters shipped to France by air from

Madagascar have arrived in fresh condition when packed 13 lbs (6 kg) to

the carton and cushioned with leaves of the traveler's tree (Ravenala

madagascariensis Sonn.).

Boat shipment requires hydrocooling at

the plantation at 32º-35.6º F (0º-2º C), packing in

sealed polyethylene bags, storing and conveying to the port at -4º

to -13º F (-20º--25º C) and shipping at 32º to

35.6º F (0º-2º C).

In Florida, fresh lychees in

sealed, heavy-gauge polyethylene bags keep their color for 7 days in

storage or transit at 35º to 50º F (1.67º-10º C).

Each bag should contain no more than 15 lbs (6.8 kg) of fruit.

Lychees

placed in polyethylene bags with moss, leaves, paper shavings or cotton

packing have retained fresh color and quality for 2 weeks in storage at

45º F (7.22º C); for a month at 40º F (4.44º C). At

32º to 35º F(0º-1.67º C) and 85% to 90% relative

humidity, untreated lychees, can be stored for 10 weeks; the skin will

turn brown but the flesh will be virtually in fresh condition but

sweeter.

Frozen, peeled or unpeeled, lychees in moisture-vapor-proof containers keep for 2 years.

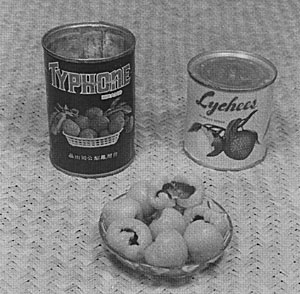

Plate XXXIII: LYCHEE, Litchi chinensis: dried

Drying of Lychees

Lychees

dehydrate naturally. The skin loses its original color, becomes

cinnamon-brown, and turns brittle. The flesh turns dark-brown to nearly

black as it shrivels and becomes very much like a raisin. The skin of

'Kwai Mi' becomes very tough when dried; that of 'Madras' less so. The

fruits will dry perfectly if clusters are merely hung in a closed,

air-conditioned room.

In China, lychees are preferably dried in

the sun on hanging wire trays and brought inside at night and during

showers. Some are dried by means of brick stoves during humid weather.

When

exports of dried fruits from China to the United States were suspended,

India welcomed the opportunity to supply the market. Experimental

drying involved preliminary disinfection by immersing the fruits in

0.5% copper sulphate solution for 2 minutes. Sun-drying on coir-mesh

trays took 15 days and the results were good except that thin-skinned

fruits tended to crack. It was found that shade-drying for 2 days

before full exposure to the sun prevented cracking.

Electric-oven

drying of single layers arranged in tiers, at 122º to 140º F

(50º-65º C), requires only 4 days. Hot-air-blast at 160º

F(70º C) dries seedless fruits in 48 hours. Fire-oven and

vacuum-oven drying were found unsatisfactory. Florida researchers have

demonstrated the feasibility of drying untreated lychees at 120º F

(48.8º C) with free-stream air flow rates above 35 CMF/f2. Drying

at higher temperatures gave the fruits a bitter flavor.

The best

quality and light color of flesh instead of dark-brown is achieved by

first blanching in boiling water for 5 minutes, immersing in a solution

of 2% potassium metabisulphite for 48 hours, and dipping in citric acid

prior to drying.

Dried fruits can be stored in tins at room temperature for about a year with no change in texture or flavor.

Pests

In most areas where lychees are grown, the most serious foliage pest is the erinose, or leaf-curl, mite, Aceria litchii,

which attacks the new growth causing hairy, blister-like galls on the

upperside of the leaves, thickening, wrinkling and distorting them, and

brown, felt-like wool on the underside. The mite apparently came to

Florida on plants from Hawaii in 1953 but has been effectively

eradicated. A leaf-webber, Dudua aprobola, attacks the new growth of all lychee trees in the Punjab.

The most destructive enemy of the lychee in China is a stinkbug (Tessaratoma papillosa)

with bright-red markings. It sucks the sap from young twigs and they

often die; at least there is a high rate of fruit-shedding. This pest

is combatted by shaking the trees in winter, collecting the bugs and

dropping them into kerosene. Without such efforts, it works havoc. A

stinkbug (Banasa lenticularis) has been found on lychee foliage in Florida. The leaf-eating false-unicorn caterpillar (Schizura ipomeae), which is parasitized by a tachinid fly (Thorocera floridensis) feeds on the leaves. The foliage is sometimes infested with red spider mites (Paratetranychus hawaiiensis). The citrus aphid (Toxoptera aurantii) preys on flush foliage. Two leaf rollers, Argyroploce leucaspis, and A. aprobola, are active on lychee trees in India. Thrips (Dolicothrips idicus) attack the foliage and Megalurothrips (Taeniothrips) distalis and Lymantria mathura damage the flowers.

A twig-pruner, Hypermallus villosus, has damaged lychee trees in Florida and a twig borer, Proteoteras implicata, has killed twigs of new growth on Florida lychees. The larvae of a native leaf beetle, Exema nodulosa,

has been found puncturing and girdling lychee branchlets 1/8 to 1/4 in

(3-6 mm) thick. Ambrosia beetles bore into the stems of young trees and

fungi enter through their holes. A shoot-borer, Chlumetia transversa, is found on lychee trees all over India. Two bark-boring caterpillars, Indarbela quadrinotata and I. tetraonis, bore rings around the trunk underneath the bark of older trees. The larvae of a small moth, Acrocerops cramerella,

eat developing seeds and the pith of young twigs. A small parasitic

wasp helps to control this predator, as does the sanitary practice of

burning the fallen lychee leaves.

The aphid (Aphis spiraecola) occurs on young plants in shaded nurseries, as does the armored scale, or lychee bark scale, Pseudaulacaspis major, and white peach scale, P. pentagona. The Florida red scale, Chrysomphalus aonidum, has been seen on lychee trees, also the banana-shaped scale, Coccus acutissimus, and green-shield scale, Pulvinaria psidii. The latter is the second most serious pest in Florida. Others are the six-spotted mite, Eotetranychus sexmaculatus, the leaf-footed bug, Leptoglossus phyllopus,

and less troublesome creatures such as the several species of

Scarabaeidae (related to June bugs) which attack leaves and flower buds.

In South Africa, the parasitic nematode Hemicriconemoides mangiferae and Xiphinema brevicolle cause die-back, decline and ultimately death of lychee trees, sometimes devastating orchards. The root-knot nematode, Meloidogyne javanica, also attacks the lychee in South Africa but is less prevalent.

In Florida, the southern green stinkbug, Nezara viridula, and the larvae of the cotton square borer, Strymon metinus, attack the fruit. Seed-feeding Lepidoptera, especially Cryptophlebia ombrodelta and Lobesia

sp. cause much fruit damage and falling in northern Queensland.

Carbaryl sprays considerably reduce the losses. In South Africa, a

moth, Argyroploce peltastica,

lays eggs on the surface of the fruit and the larvae may penetrate weak

areas of the skin and infest the flesh. The fruit flies, Ceratites capitata and Pterandrus rosa make minute holes and cracks in the skin and cause internal decay.

These

pests are so detrimental that growers have adopted the practice of

enclosing bunches of clusters (with most of the leaves removed) in bags

made of "wet-strength" paper or unbleached calico 6 to 8 weeks before

harvest-time. The Caribbean fruit fly, Anastrepha suspensa, has attacked lychee fruits in Florida.

Birds,

bats and bees damage ripe fruits on the trees in China and sometimes a

stilt house is built beside a choice lychee tree for a watchman to keep

guard and ward off these predators, or a large net may be thrown over

the tree. In Florida, birds, squirrels, raccoons and rats are prime

enemies. Birds have been repelled by hanging on the branches thin

metallic ribbons which move, gleam and rattle in the wind.

Grasshoppers, crickets, and katydids may, at times, feed heavily on the

foliage.

Diseases

Few

diseases have been reported from any lychee-growing locality. The

glossy leaves are very resistant to fungi. In Florida, lychee trees are

occasionally subject to green scurf, or algal leaf spot (Cephaleuros virescens), leaf blight (Gleosporium sp.), die-back, caused by Phomopsis sp., and mushroom root rot (Clitocybe tabescens)

which is most likely to attack lychee trees planted where oak trees

formerly stood. Old oak roots and stumps have been found thoroughly

infected with the fungus.

In India, leaf spot caused by Pestalotia pauciseta may be prevalent in December and can be controlled by lime-sulphur sprays. Leaf spots caused by Botryodiplodia theobromae and Colletotrichum gloeosporioides, which begin at the tip of the leaflet, were first noticed in India in 1962.

Lichens and algae commonly grow on the trunks and branches of lychee trees.

The

main post-harvest problem is spoilage by the yeast-like organism, which

is quick to attack warm, moist fruits. It is important to keep the

fruits dry and cool, with good circulation of air. When conditions

favor rotting, dusting with fungicide will be necessary.

Fig. 73: Peeled, seeded, lychees (Litchi chinensis) are canned in sirup in the Orient and exported to the United States and other countries.

Food Uses

Lychees are most relished fresh, out-of-hand. Peeled and pitted, they are commonly added to fruit cups and fruit salads.

Lychees

stuffed with cottage cheese are served as salad topped with dressing

and pecans. Or the fruit may be stuffed with a blend of cream cheese

and mayonnaise, or stuffed with pecan meats, and garnished with whipped

cream.

Sliced lychees, congealed in lime gelatin, are served on

lettuce with whipped cream or mayonnaise. The fruits may be layered

with pistachio ice cream and whipped cream in parfait glasses, as

dessert. Halved lychees have been placed on top of ham during the last

hour of baking, or grilled on top of steak.

Pureed lychees are

added to ice cream mix. Sherbet is made by extracting the juice from

fresh, seeded lychees and adding it to a mixture of prepared plain

gelatin, hot milk, light cream, sugar and a little lemon juice, and

freezing.

Peeled, seeded lychees are canned in sugar sirup in

India and China and have been exported from China for many years.

Browning, or pink discoloration, of the flesh is prevented by the

addition of 4% tartaric acid solution, or by using 30º Brix sirup

containing 0.1% to 0.15% citric acid to achieve a pH of about 4.5,

processing for a maximum of 10 minutes in boiling water, and chilling

immediately.

| Food

Value Per

100 g of Edible Portion* |

| Fresh | Dried | | Calories | 63-64 | 277 | | Moisture | 81.9-84.83% | 17.90-22.3% | | Protein | 0.68-1.0 g | 2.90-3.8 g | | Fat | 0.3-0.58 g | 0.20-1.2 g | | Carbohydrates | 13.31-16.4 g | 70.7-77.5 g | | Fiber | 0.23-0.4 g | 1.4 g | | Ash | 0.37-0.5 g | 1.5-2.0 g | | Calcium | 8-10 mg | 33 mg | | Phosphorus | 30-42 mg | | | Iron | 0.4 mg | 1.7 mg | | Sodium | 3 mg | 3 mg | | Potassium | 170 mg | 1,100 mg | | Thiamine | 28 mcg | | | Nicotinic Acid | 0.4 mg | | | Riboflavin | 0.05 mg | 0.05 mg | | Ascorbic Acid | 24-60 mg | 42 mg |

*According to analyses made in China, India and the Philippines. |

|

The lychee is low in phenols and non-astringent in all stages of maturity.

To

a small extent, lychees are also spiced or pickled, or made into sauce,

preserves or wine. Lychee jelly has been made from blanched, minced

lychees and their accompanying juice, with 1% pectin, and combined

phosphoric and citric acid added to enhance the flavor.

The

flesh of dried lychees is eaten like raisins. Chinese people enjoy

using the dried flesh in their tea as a sweetener in place of sugar.

Whole frozen lychees are thawed in tepid water. They must be consumed very soon, as they discolor and spoil quickly.

Other Uses

In

China, great quantities of honey are harvested from hives near lychee

trees. Honey from bee colonies in lychee groves in Florida is light

amber, of the highest quality, with a rich, delicious flavor like that

of the juice which leaks when the fruit is peeled, and the honey does

not granulate.

Medicinal Uses: Ingested in moderate amounts, the

lychee is said to relieve coughing and to have a beneficial effect on

gastralgia, tumors and enlargements of the glands. One stomach-ulcer

patient in Florida, has reported that, after eating several fresh

lychees he was able to enjoy a large meal that, ordinarily, would have

caused great discomfort. Chinese people believe that excessive

consumption of raw lychees causes fever and nosebleed. According to

legends, ancient devotees have consumed from 300 to 1,000 per day.

In

China, the seeds are credited with an analgesic action and they are

given in neuralgia and orchitis. A tea of the fruit peel is taken to

overcome smallpox eruptions and diarrhea. In India, the seeds are

powdered and, because of their astringency, administered in intestinal

troubles, and they have the reputation there, as in China, of relieving

neuralgic pains. Decoctions of the root, bark and flowers are gargled

to alleviate ailments of the throat. Lychee roots have shown activity

against one type of tumor in experimental animals in the United States

Department of Agriculture/National Cancer Institute Cancer Chemotherapy

Screening Program.

|

|