Publication

from Agroforestree Database: a tree reference and selection guide

version 4.0

by C. Orwa, A. Mutua, R. Kindt, R. Jamnadass and S. Anthony

Litchi chinensis Sonn.

Local Names: Bengali (lichi);

Chinese (lizi, jingli, huoshan, danli); English (lychee

nut, litchi, lychee); French (quenèpe chinois, quenepier chinois, litchi de

chine, litchi, cerisier de la Chine); German (Chinesische

Haselnuß, litchipflaume); Hindi (lici, licy, lichi); Indonesian

(klengkeng litsi, kalengkeng); Javanese (klengkeng); Khmer (kuléén); Lao

(Sino-Tibetan) (ngèèw); Malay (laici, kelengkang); Spanish (leché);

Trade name (lichi, lychee); Vietnamese (vai, cây vai, tu hú)

Family: Sapindaceae

Botanic

Description

Litchi chinensis is a

handsome, dense, round-topped tree with a smooth, grey, trunk and

limbs. Under ideal conditions it may reach 12 m high, but is usually

much smaller.

Leaves leathery, pinnate, divided into 4-8 pairs

of elliptic or lanceolate, acuminate, glabrous leaflets, 5-7 cm long,

reddish when young, becoming shiny and bright green.

Inflorescence

a many-branched panicle, 5-30 cm long, many flowered; flowers small,

yellowish-white, functionally male or female; calyx tetramerous;

corolla absent.

Fruit covered by a rough leathery rind or

pericarp, pink to strawberry red. Fruit oval, heart shaped or nearly

round, 2.5 cm or more in diameter. The edible portion or aril is white,

translucent, firm and juicy. Flavour sweet, fragrant and delicious.

Inside the aril is a seed that varies considerably in size. The most

desirable varieties contain atrophied seeds called ‘chicken tongue’.

These are very small, up to 1 cm in length. Larger seeds vary between 1

and 2 cm in length and are plumper than the chicken tongues. There is

also a distinction between the lychee that leaks juice when the skin is

broken and the ‘dry and clean’ varieties that are more desirable.

The specific name, ‘chinensis’, is Latin for ‘Chinese’.

Biology

L. chinensis

requires seasonal temperature variations for best flowering and

fruiting. Warm, humid summers are best for flowering and fruit

development, and a certain amount of winter chilling is necessary for

flower-bud development. Usually male flowers appear first, then the

females and imperfect bisexual flowers. Pollination is effected by a

number of insects including flies, ants and wasps, but bees are very

effective.

Ecology

L. chinensis

is one of the most environmentally sensitive of the tropical tree

crops. It is adapted to the tropics and warm subtropics, producing best

in regions with winters that are short, dry and cool but frost free,

and summers that are long and hot with high rainfall. Good protection

from wind is essential for cropping. Year-to-year variations in weather

precipitate crop failures, for example, through untimely rain promoting

flushing at the expense of floral development, or through poor fruit

set following damp weather during bloom.

Biophysical

Limits

Mean annual temperature: 20-25 deg. C, Mean annual rainfall: 1500 mm

Soil

type: The tree needs well-drained soil that is rich in organic matter.

A soil pH between 5.5 and 7.5 is acceptable, but plants grow much

better in soils with a pH at the low end of this range.

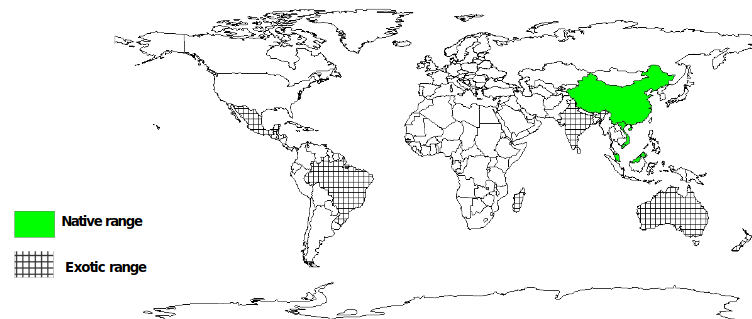

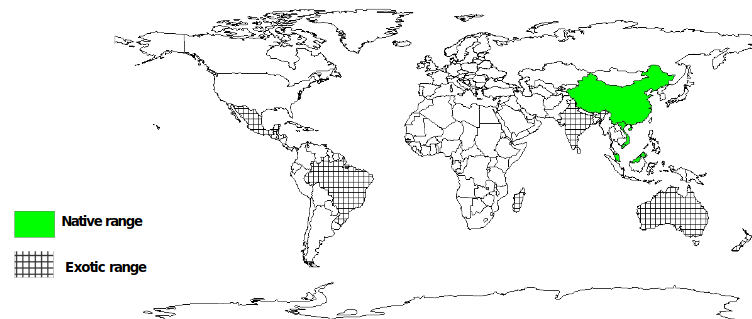

Documented

Species Distribution

Native: China, Malaysia, Vietnam

Exotic: Australia,

Brazil, Honduras, Hong Kong, India, Israel, Madagascar, Mauritius,

Mexico, Myanmar, New Zealand, Reunion, South Africa, Taiwan, Province

of China, Thailand, US, Zanzibar

The

map above shows countries where the species has been planted. It does

neither suggest that the species can be planted in every ecological

zone within that country, nor that the species can not be planted in

other countries than those depicted. Since some tree species are

invasive, you need to follow biosafety procedures that apply to your

planting site.

Products

Food: The juicy aril is the

edible part of the lychee. It may be eaten fresh or juiced, preserved

in syrup and canned, dried or frozen. Lychee nuts are fruit that has

been dried, either artificially or in the sun. The food value of lychee

lies in its sugar content, which ranges from 7 to 21%, depending on

climate and cultivar. Fruit also contains about 0.7% protein, 0.3% fat,

0.7% minerals (particularly calcium and phosphorus) and is a reasonable

source of vitamins C (64 mg/100 g pulp), A, B1 and B2. The strong

appeal of lychee lies in the exquisite aroma of the fruit.

Apiculture: This tree is

widely grown for instance in Singapore and Mauritius as a major honey

source. The honey is of excellent quality and flavour.

Timber: The wood is said to be nearly indestructible, although it is brittle and has few uses.

Tannin or

dyestuff: Bark contains tannin.

Medicine: The fruit, its peel

and the seed are used in traditional medicine; decoctions of the root,

bark and flowers are used as a gargle. Seeds are used as an anodyne in

neuralgic disorders and orchitis.

Alcohol: Lychee fruit can be processed into wine.

Services

L. chinensis trees are

beautiful in spring, when they are covered with huge sprays of flowers;

they are also an attractive sight when in full fruit. These

characteristics make it a popular ornamental tree in parks and gardens.

Tree

Management

L. chinensis

needs full sun, but young trees must be protected from heat, frost and

high winds. The trees need warmth and a frost-free environment but can

often withstand light freezes with some kind of overhead protection.

When plants are young, shelter can be provided by building a frame

around them and covering it with straw or plastic sheeting. Electric

light bulbs can also be used for added warmth.

The trees will

not tolerate standing water but require very moist soil, so they should

be watered regularly when growing actively. The trees are very

sensitive to damage from salts in the soil or in water. The soil should

be leached regularly in saline soil areas. Chelated iron and sulphur

may be necessary in areas with alkaline soils. Young trees should

receive only light applications of a complete fertilizer. Mature trees

are heavier feeders and should be fertilized regularly.

Cincturing

has been used commercially in China, Thailand, Australia, Florida and

Hawaii to impose shoot rest and improve flowering and fruiting. Trees

are cinctured after completion of the postharvest flush, if they are

healthy and flushed actively. Young trees are pruned to establish a

strong, permanent structure for easy harvest. After that, removing

crossing or damaged branches is all that is necessary, although the

trees can be pruned more heavily to control size; V-shaped crotches

should be avoided because of the wood’s brittle nature.

Growing L. chinensis

from seed needs care and promptness, because seeds soon lose their

viability if permitted to dry after removal from the fruit. The seeds

germinate without pretreatment when sown fresh. Young seedlings grow

vigorously until they reach 24-30 cm.

Air-layering is the most

common method of propagation, and rates of success are usually not less

than 95%. Other methods of propagation include grafting (useful for

top-working older trees), budding and use of cuttings (for the rapid

multiplication of new cultivars). Incompatibility occurs in some scion

and root-stock combinations. Wedge and bud grafts are possible, but

seldom used.

L. chinensis is one of the

most environmentally sensitive of the tropical tree crops. It is

adapted to the tropics and warm subtropics, producing best in regions

with winters that are short, dry and cool but frost free, and summers

that are long and hot with high rainfall. Good protection from wind is

essential for cropping. Year-to-year variations in weather precipitate

crop failures, for example, through untimely rain promoting flushing at

the expense of floral development, or through poor fruit set following

damp weather during bloom.

Germplasm

Management

Seed storage behaviour is recalcitrant; storing seed in moist peat moss

at 8 deg. C is recommended. Viability is reduced from 100% to less than

20% on desiccation to about 20% mc, and no seeds remain viable when mc

is reduced below this value. There is complete loss in viability after

7 days of open storage at 30 deg. C; however, viability of seed stored

moist at 5 deg. C was maintained for 60 and at 30 deg. C for 100 days.

Germination rate was 92% after 7 weeks of moist storage at 8-10 deg. C

with 100% rh and with 80% nitrous oxide plus 20% oxygen; 69% after 280

days moist storage at 15 deg. C in moist (20% mc) perlite, plus

chlorthalonil. Excised embryonic axes tolerate desiccation to 30% mc.

Seeds extracted from fruit harvested at 98 days after anthesis are more

tolerant of desiccation than those from overripe or immature fruit.

Pests and

Diseases

Mites, scale insects and aphids occasionally infest L. chinensis.

Both immature and ripe fruit attract birds, so it may be necessary to

cover the plants with protective netting. Other pests include the

macadamia-nut borer, macadamia-flower caterpillar, fruit fly, fruit

bats and erisone mites. A parasitic alga (Cephaleuros spp.) occasionally attacks trees, causing loss of vigour. Diseases recorded include bark canker and brown leaf felting.

Further

Reading

Anon. 1986. The useful plants of India. Publications & Information Directorate, CSIR, New Delhi, India.

Crane E, Walker P. 1984. Pollination directory for world crops. International Bee Research Association, London, UK.

FAO. 1982. Fruit-bearing forest trees: technical notes. FAO-Forestry-Paper. No. 34. 177 pp.

Glenn T. 1987. Tropical fruit: an Australian guide to growing and using exotic fruits. Penguin Books Australia.

Hong TD, Linington S, Ellis RH. 1996. Seed storage behaviour: a compendium. Handbooks for Genebanks: No. 4. IPGRI.

International Board for Plant Genetic Resources (IBPGR). 1986. Genetic Resources of Tropical and sub-Tropical Fruits and Nuts.

Lanzara P. and Pizzetti M. 1978. Simon & Schuster's Guide to Trees. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Lemmens

RHMJ, Soerianegara I, Wong WC (eds.). 1995. Plant Resources of

South-east Asia. No 5(2). Timber trees: minor commercial timbers.

Backhuys Publishers, Leiden.

Luna RK. 1996. Plantation trees. International Book Distributors, Dehra Dun, India.

Nicholson B.E, Harrison S.G, Masefield G.B & Wallis M. 1969. The Oxford Book of Food Plants. Oxford University Press.

Verheij

EWM, Coronel RE (eds.). 1991. Plant Resources of South East Asia No 2.

Edible fruits and nuts. Backhuys Publishers, Leiden.

Williams R.O & OBE. 1949. The useful and ornamental plants in Zanzibar and Pemba. Zanzibar Protectorate.

Young JA, Young CG. 1992. Seeds of woody plants in North America. Dioscorides Press, Oregon, USA.

|

|