Publication

from Agroforestree Database: a tree reference and selection guide

version 4.0

by C. Orwa, A. Mutua, R. Kindt, R. Jamnadass and S. Anthony

Persea americana Miller

Local Names: Amharic (avocado);

Burmese (kyese, htaw bat); Creole (zaboka); English (butter

fruit, avocado, avocado-pear, alligator pear); Filipino (avocado); French

(avocat, avocatier, zaboka, zabelbok); German

(Alligatorbirne, Avocadobirne); Indonesian (avokad, adpukat); Khmer

(avôkaa); Malay (apukado, avokado); Mandinka (avacado); Pidgin English

(bata); Spanish (pagua, aguacate); Swahili (mparachichi, mpea, mwembe

mafuta); Thai (awokado); Trade names (medang); Vietnamese (bo, lê dâù)

Family: Lauraceae

Botanic

Description

Persea americana is a

medium to large tree, 9-20 m in height. The avocado is classified as an

evergreen, although some varieties lose their leaves for a short time

before flowering. The tree canopy ranges from low, dense and

symmetrical to upright and asymmetrical.

Leaves are 7-41 cm in

length and variable in shape (elliptic, oval, lanceolate). They are

often pubescent and reddish when young, becoming smooth, leathery, and

dark green when mature.

Flowers are yellowish green, and 1-1.3

cm in diameter. The many-flowered inflorescences are borne in a

pseudo-terminal position. The central axis of the inflorescence

terminates in a shoot.

The fruit is a berry, consisting of a

single large seed, surrounded by a buttery pulp. It contains 3-30% oil

(Florida varieties range from 3-15%). The skin is variable in thickness

and texture. Fruit colour at maturity is green, black, purple or

reddish, depending on variety. Fruit shape ranges from spherical to

pyriform, and weigh up to 2.3 kg.

Biology

Varieties are

classified into A and B types according to the time of day when the

female and male flower parts become reproductively functional. New

evidence indicates avocado flowers may be both self- and

cross-pollinated. Self-pollination occurs during the second flower

opening when pollen is transferred to the stigma while

cross-pollination may occur when female and male flowers from A and B

type varieties open simultaneously. Self-pollination appears to be

primarily caused by wind, whereas cross-pollination may be effected by

large flying insects such as bees and wasps. Varieties vary in the

degree of self- or cross-pollination necessary for fruit set. Some

varieties, such as 'Waldin', 'Lula' and 'Taylor' fruit well in solid

plantings. Others, such as 'Pollock' and 'Booth 8' (both B types) do

not, and it is probably advantageous to plant them in rows alternating

with other varieties (A types) which bloom simultaneously to facilitate

adequate pollination.

Ecology

West Indian and some

hybrid varieties are best adapted to a lowland tropical climate and

relatively frost-free areas of the subtropics. Mexican varieties are

more cold tolerant and not well adapted to lowland tropical conditions.

Guatemalan x Mexican hybrids are generally more cold tolerant than West

Indian x Guatemalan hybrid varieties. Some of the more cold-tolerant

varieties in Florida include 'Brogdon', 'Gainesville', 'Mexicola', and

'Winter Mexican'. However, it may be difficult to find plants of these

varieties. Moderately cold-tolerant types include 'Tonnage',

'Choquette', 'Hall', 'Lula', 'Taylor', 'Monroe', and 'Brookslate'.

Varieties with little cold-tolerance include 'Simmonds', 'Pollock',

'Dupuis', 'Nadir', 'Hardee' and 'Waldin'.

Biophysical

Limits

Altitude: 0-2 500 m, Mean annual temperature: -4 to 40 deg. C, Mean annual rainfall: 300-2 500 mm

Soil

type: Requires a well-drained aerated soil because the roots are

intolerant of anaerobic conditions; waterlogging for more than 24 hours

can kill trees. A pH of 5-5.8 is optimal for growth and fruit yield.

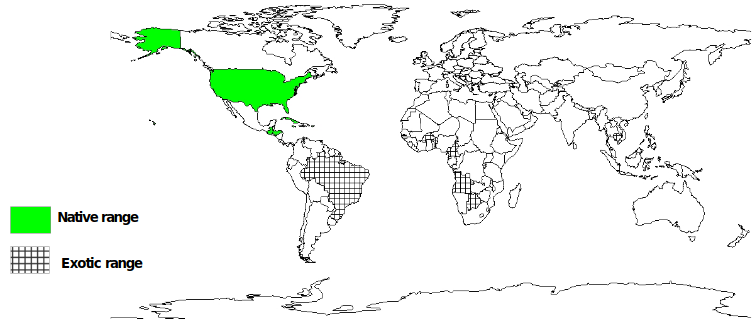

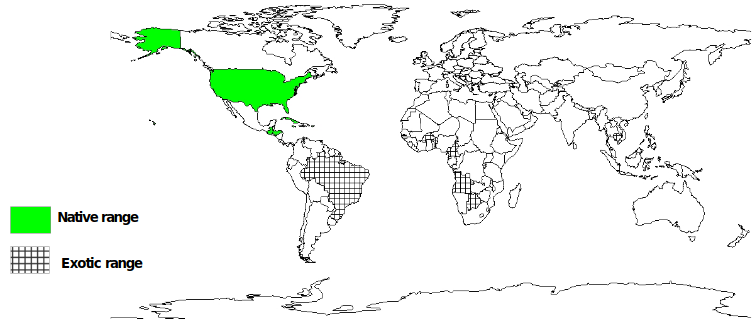

Documented

Species Distribution

Native: Antigua and Barbuda,

Barbados, Cuba, Dominica, Dominican Republic, Grenada, Guatemala,

Honduras, Jamaica, Puerto Rico, St Lucia, St Vincent and the

Grenadines, Trinidad and Tobago, United States of America, Virgin

Islands (US)

Exotic:

Angola, Benin, Botswana, Brazil, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cambodia,

Cameroon, Cape Verde, Central African Republic, Chad, Chile, Congo,

Cote d'Ivoire, Democratic Republic of Congo, Djibouti, Egypt,

Equatorial Guinea, Ethiopia, Gabon, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea,

Guinea-Bissau, Haiti, India, Indonesia, Israel, Kenya, Lesotho,

Liberia, Madagascar, Malawi, Malaysia, Mali, Mauritania, Mexico,

Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Papua New Guinea, Rwanda, Sao Tome

et Principe, Seychelles, Sierra Leone, Somalia, South Africa, Sudan,

Swaziland, Tanzania, Thailand, Togo, Uganda, Vietnam, Zambia, Zanzibar,

Zimbabwe

The

map above shows countries where the species has been planted. It does

neither suggest that the species can be planted in every ecological

zone within that country, nor that the species can not be planted in

other countries than those depicted. Since some tree species are

invasive, you need to follow biosafety procedures that apply to your

planting site.

Products

Food: The tree is grown for its

nutritious fruit that has long been important in the diets of the

people of Central America. Consumption is most often as an uncooked

savoury dish mixed with herbs and/or spices, as an ingredient of

vegetable salads, or as a sweetened dessert. However, its texture and

colour can be used to enhance the presentation and consumption of many

foods. Cooking impairs flavour and appearance of avocados. The flesh

represents 65-75% of the total fruit weight. The contents vary widely

in different cultivars. The approximate content per 100 g of edible

portion are: water 65-86 g, protein 1-4 g (unusually high for fruit),

fat 5.8-23 g (largely mono-saturated and documented as an

anti-cholesterol agent), carbohydrates 3.4-5.7 g (of which sugars only

1 g), iron 0.8-1 g, vitamin A and vitamin B-complex 1.5-3.2 mg. The

energy value is 600-800 kJ/100 g. The high oil content of the mature

fruit gives the flesh a buttery texture which is neither acid nor

sweet. The easily digestible flesh is rich in iron and vitamins A and

B; providing a highly nutritious solid food, even for infants.

Fodder: Surplus fruit is an important food source for pigs and other livestock.

Apiculture: Bees, important for

pollination and honey production, visit the avocado tree. The honey

produced is dark with a heavy body.

Timber: Wood of Persea

has been used for house building (especially for house posts), light

construction, furniture, cabinet making, agricultural implements,

carving, sculptures, musical instruments, paddles, small articles like

pen and brush holders, and novelties. It also yields a good-quality

veneer and plywood. More popular for its fruits the wood of avocado is

seldom used. The wood is brittle and susceptible to termite attack.

Lipids: The pulp and the seeds

contain fatty acids, such as oleic, lanolic, palmitic, stearic,

linoleic, capric and miristic acid which constitutes 80% of the fruits

fatty content. The oil is used by the cosmetic industry in soaps and

skin moisturizer products.

Poison: The unripe fruit is poisonous and the ground-up seed mixed with cheese is used as a rat and mouse poison.

Medicine: Recently

anti-cancerous activity has been reported in extracts of leaves and

fresh shoots of avocado. Oil extracted from the seeds has astringent

properties, and an oral infusion of the leaves is used to treat

dysentery. The skin of the fruit has anti-helmintic properties. The

avocado is also said to have spasmolitic and abortive properties. The

seed is ground and made into an ointment used to treat various skin

afflictions, such as scabies, purulent wounds, lesions of the scalp and

dandruff. The flesh is also used in traditional medicine.

Essential oil: Watery extracts of the avocado leaves contain a yellowish-green essential oil.

Tree

Management

Planting

distances depend on soil type and fertility, current technology, and

economic factors. In commercial groves, trees are planted from 5-7 m in

rows and 7-9 m between rows. Pruning during the first 2 years

encourages lateral growth and multiple framework branching.

Commercially, after several years of production it is desirable to

occasionally reduce canopy width of the trees to 5-6 m, to reduce

spraying and harvesting costs and reduce storm damage. Severe topping

and hedging do not injure trees. Planned tree removal is an option that

should be seriously considered for commercial plantings. An avocado

tree grown for its fruit production should either be from budded or

grafted trees that will produce fruit within 2 or 3 years as compared

to the 8-10 or more years required of seedling avocados. The fruit does

not generally ripen until it falls or is picked from the tree. Strong

winds or a heavy crop easily breaks limbs.

Germplasm

Management

The

seeds are recalcitrant; lowest safe mc is 57% mc for slow-drying, 57.4%

mc for rapid drying; are only viable for 2-3 weeks after removal of the

fruits. Storage is however possible in using several methods such as, 8

months in dry peat at 5 deg. C provided they are not permitted to dry

out, or for several months by dusting seeds with copper fungicide and

storing in damp sawdust or peat in airtight bags at 4-5 deg. C. A

germination percentage of 53-75% was observed after 1 year in moist

storage and fungicide at 4.4 deg. C.

Pests and

Diseases

Many

insect pests attack avocados but they seldom limit fruit production

significantly. Currently, the most important insect pests are avocado

looper (Epimecis detexta), pyriform scale (Protopulvinaria pyriformis), dictyospermum scale (Chrysomphalus dictyospermi), avocado red mites (Oligonychus yothersi), borers (Ambrosia beetles, Xylosandrus spp.), avocado lace bugs (Acysta perseae), and red-banded thrips (Selenothrips rubrocinctus).

Successful

control of foliar and fruit diseases caused by fungi requires that all

susceptible parts of the plant be thoroughly coated with the fungicide

before infection occurs. Sprays must be re-applied as new tissues

become exposed by growth and as spray residues are reduced by

weathering.

Trees in areas with poorly drained soils and/or which

are subject to flooding are likely to be affected by avocado root rot.

This is the most serious disease in most avocado-producing areas of the

world. Although many trees are infected with the fungus, the disease

only appears to be serious if trees are subjected to flooded

conditions. Leaves of infected trees may be pale green, wilted, and

necrotic and terminal branches die back in advanced stages of the

disease. Feeder roots become darkened and decayed and severely affected

trees usually die.

Sun-blotch (caused by a viroid) where symptoms of

infection include sunken yellow or whitish streaking or spotting and

distortion of twigs, leaves, and fruit, is transmitted through buds,

seeds, and root-grafting of infected trees. There is no control for

this disease, and infected trees should be destroyed. Algal leaf spot

whose symptoms appear first on upper leaf surfaces as green,

yellowish-green, or rust coloured roughly circular spots. Diplodia

stem-end rot begins at the stem end of the fruit and develops as the

fruit softens. Usually only a problem with immature fruit after harvest

and can be prevented by harvesting only mature fruit.

Cercospora

spot infection appears on fruits and leaves as small, angular, dark

brown spots with a yellow halo, which coalesce to form irregular

patches. Fruit lesions are frequently the points of entry for other

decay organisms such as the anthracnose fungus.

Avocado scab (the

scab fungus) readily infects young, succulent tissues of leaves, twigs

and fruit. These tissues become resistant as they mature. Lesions

appear as small, dark spots visible on both sides of the leaves. Spots

on leaf veins, petioles and twigs are slightly raised, and oval to

elongated. Severe infections distort and stunt leaves.

Spots on

fruits are dark, oval and raised and eventually coalesce to form

cracked and corky areas, which impair the appearance but not the

internal quality of the fruit. Begin a spray program for scab

prevention when bloom buds begin to swell and continue until harvest.

Further

Reading

Anon. 1986. The useful plants of India. Publications & Information Directorate, CSIR, New Delhi, India.

Bekele-Tesemma

A, Birnie A, Tengnas B. 1993. Useful trees and shrubs for Ethiopia.

Regional Soil Conservation Unit (RSCU), Swedish International

Development Authority (SIDA).

Cobley L.S & Steele W.M. 1976. An Introduction to the Botany of Tropical Crops. Longman Group Limited.

Crane E (ed.). 1976. Honey: A comprehensive survey. Bee Research Association.

Crane

E, Walker P. 1984. Pollination directory for world crops. International

Bee Research Association, London, UK.FAO. 1986. Some medicinal plants

of Africa and Latin America.

FAO Forestry Paper. 67. Rome.

Hong TD, Linington S, Ellis RH. 1996. Seed storage behaviour: a compendium. Handbooks for Genebanks: No. 4. IPGRI.

ICRAF.

1992. A selection of useful trees and shrubs for Kenya: Notes on their

identification, propagation and management for use by farming and

pastoral communities. ICRAF.

Katende AB et al. 1995. Useful trees

and shrubs for Uganda. Identification, Propagation and Management for

Agricultural and Pastoral Communities. Regional Soil Conservation Unit

(RSCU), Swedish International Development Authority (SIDA).

Lanzara P. and Pizzetti M. 1978. Simon & Schuster's Guide to Trees.

New York: Simon and Schuster.

Lemmens

RHMJ, Soerianegara I, Wong WC (eds.). 1995. Plant Resources of

South-east Asia. No 5(2). Timber trees: minor commercial timbers.

Backhuys Publishers, Leiden.

Mbuya LP et al. 1994. Useful trees and

shrubs for Tanzania: Identification, Propagation and Management

for Agricultural and Pastoral Communities. Regional Soil Conservation

Unit (RSCU), Swedish International Development Authority (SIDA).

Nicholson B.E, Harrison S.G, Masefield G.B & Wallis M. 1969. The Oxford Book of Food Plants. Oxford University Press.

Noad T, Birnie A. 1989. Trees of Kenya. General Printers, Nairobi.

Peter G von Carlowitz.1991. Multipurpose Trees and Shrubs-Sources of Seeds and Innoculants. ICRAF. Nairobi, Kenya.

Purseglove

JW. 1972. Tropical crops: Monocotyledons 2. Longman Group Ltd, UK.Sam.

1967. Avocado growing in Ghana. World crops. 2(5): 273-274.

Sosef

MSM, Hong LT, Prawirohatmodjo S. (eds.). 1998. PROSEA 5(3) Timber

trees: lesser known species. Backhuys Publishers, Leiden.

Timyan J. 1996. Bwa Yo: important trees of Haiti. South-East Consortium for International Development. Washington D.C.

Verheij

EWM, Coronel RE (eds.). 1991. Plant Resources of South East Asia No 2.

Edible fruits and nuts. Backhuys Publishers, Leiden.

Williams R.O & OBE. 1949. The useful and ornamental plants in Zanzibar and Pemba. Zanzibar Protectorate

|

|